New research using decades of monitoring environmental data available through TERN’s environmental data collection methods has identified significant problems with historic fire management in one of Australia’s premier National Parks: Kakadu. Despite the data painting a somewhat negative picture of the past, the research proposes economically viable carbon-market based solutions and vindicates recent park management actions that are delivering more sustainable and ecologically appropriate fire management in the reserve.

|

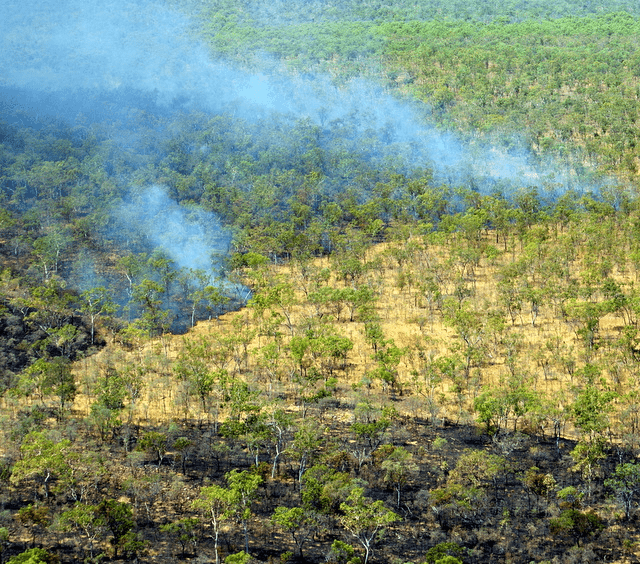

| New research using TERN data indicates that the impact of fire on the ecology in Kakadu National Park was “more dire than previously thought” |

New research has evaluated the historic state of fire management for biodiversity conservation in Australia’s premier savanna reserve, Kakadu National Park.

The assessment, just published in Ecosphere, draws on long-term data on fire incidence and severity, and vegetation and fauna collected at the 220 monitoring plots of the Three Parks Savanna Fire Effects Plot Network, part of TERN’s Long Term Ecological Research Network (LTERN).

To assess management effectiveness of historic fire management practices in the National Park, researchers used LTERN data combined with satellite-derived fire and habitat mapping data to model responses of vegetation and fauna.

“We now know that fire regimes up until the end of 2015, especially the high frequency of large, relatively severe late season fires, may have contributed to the declines in small mammals and impacted fire-sensitive flora across Northern Australia,” says Mr Jay Evans of Charles Darwin University’s Darwin Centre for Bushfire Research.

“But the performance metrics we used to quantify this indicate that the impact of fire on the ecology in the reserve was more dire than previously thought.”

Beyond the threshold: quantifying unsustainable fire management

The research team used ecological performance threshold metrics to assess how past fire regimes impacted on Kakadu’s ecology. A series of thresholds, or ecological tipping points, relating to fire’s impact on Kakadu’s ecosystems were assigned and the data used to assess their status. Moving beyond a threshold indicates significant ecological impact.

“Of 14 assessed performance threshold metrics, two were within acceptable thresholds at the end of 2015, and none had improved materially over the decadal assessment period,” report Jay and his co-authors in the paper.

“For example, by the end of 2015 it was observed that just 6% of woodland habitat in lowland and 23% in upland situations had remained unburnt for longer than three years and 98% of mapped fires in lowland and 87% in upland habitats were >1 km2 in extent.”

Essential research for sustainable fire management

Despite the data painting a somewhat negative picture of the past, the research vindicates park management actions over the past two years that are delivering more sustainable and ecologically appropriate fire management in the reserve.

“Our research has shown that areas which experience low intensity fires earlier in the dry season are more ecologically healthy than those impacted by late season severe fires,” says Professor Jeremy Russell-Smith, also of the Darwin Centre for Bushfire Research and Co-Leader of the Three Parks Savanna Fire-Effects Plot Network within LTERN.

“By prescribed burning areas of the parks early in the dry season, park managers are already reducing the extent of fires later in the season,” says Jeremy.

“Park managers are working closely with the scientists, statisticians, rangers, Aboriginal custodians, school and university students, and agronomists conducting research across the Three Parks Savanna Fire Effects Plot Network.

“There are cost savings for management agencies, but more importantly this inclusiveness means that park managers understand fires in savannas and how they affect biodiversity, and are better placed to implement appropriate management in policy and practice.”

|  |  |

| Low intensity fires earlier in the dry season (centre and right) are more ecologically healthy than late season severe fires (left) (images courtesy Jay Evans) | ||

Savanna burning greenhouse gas emissions abatement projects need to be further explored

But, such seasonally intensive, fine-grained adaptive fire management for biodiversity conservation is incredibly difficult and expensive. So, in addition to creating a more environmentally sustainable fire management program, the research also recommends landscape-scale carbon sequestration and savanna burning emissions abatement projects as an additional management tool.

“We are very keen to further promote formal carbon-market savanna burning approaches in the Northern Territory, similar to those undertaken in Western Arnhem Land through the West Arnhem Land Fire Abatement [WALFA] project, which have proven very successful environmentally, economically and culturally,” says Jeremy.

Under WAFMA ConocoPhillips pays around $1million a year to Indigenous ranger groups to undertake savanna fire management to offset the carbon emissions from its liquefied natural gas plant in Darwin Harbour. Since 2006 the project has abated over 100,000 tonnes of CO2 annually—equivalent to around 14,000 homes’ electricity use for a year.

“Projects like this, and indeed the ones currently being established by Kakadu’s traditional Aboriginal landowners and the park management agency, provide traditional custodians and knowledge-holders with a very viable means to stay on the land they care for and earn an income from it in the new carbon economy,” says Jeremy.

The ongoing challenge of managing Australia’s fire-prone Top End

As the researchers point out in their paper, “the substantial technical and operational fire management challenges identified here are not unique to Kakadu.”

More than 50% of substantial areas of north Australia’s 460,000-km2 mesic savannas (>1000 mm mean annual rainfall) are currently burnt annually, mostly in extensive late dry season fires.

Considering this, and the fact that extreme fires are likely to become more frequent in Australia, it is essential that the long-term collection of fire ecology data within Northern Australia is continued. Without the appropriate resourcing that will ensure the continuity and availability of long-term biodiversity and vegetation data the potential for ongoing collaboration of scientists and conservation and research agencies is severely undermined.

- This research draws on the data collected from the 220 permanent monitoring plots of the Three Parks Savanna Fire Effects Plot Network, a member of TERN’s Long Term Ecological Research Network (LTERN).

- Data on fire incidence and severity, and vegetation and fauna across habitats in Litchfield, Kakadu and Nitmiluk national parks are available via TERN’s Data Discovery Portal and the LTERN data portal.

Kakadu’s sandstone country illustrating prescribed protective burning early in the dry season using creeklines to help break up the country (image courtesy of Jeremy Russel-Smith)

Kakadu’s striking sandstone country with endemic Allosyncarpia monsoon forest (dark green) and sandstone heath (short vegetation on sides of rock formation), which is listed as an endangered vegetation community due to ecologically unsustainable contemporary fires regimes (image courtesy of Jeremy Russell-Smith)

Published in TERN newsletter August 2017