Technological advances in ecology are facilitating a deeper understanding of the habits of nocturnal hunting spiders in Australia.

For her honours year, TERN project officer Tamara Potter joined University of Sydney’s Professor Chris Dickman and Dr Aaron Greenville at the Desert Ecology Research Group to investigate camera trapping as a tool to monitor nocturnal spiders. This study presents a significant case for the application of technological advances in ecology to facilitate a deeper understanding of the habits of invertebrate fauna.

Invertebrates dominate the animal world in terms of abundance, diversity and biomass. They play a critical role in maintaining ecosystem function by performing basic services such as energy and nutrient cycling, pollination, herbivory and seed dispersal. However, despite their obvious importance, there is a disproportionate focus in many areas of research on vertebrate fauna, and our knowledge and understanding of the ecology of invertebrates is still lacking.

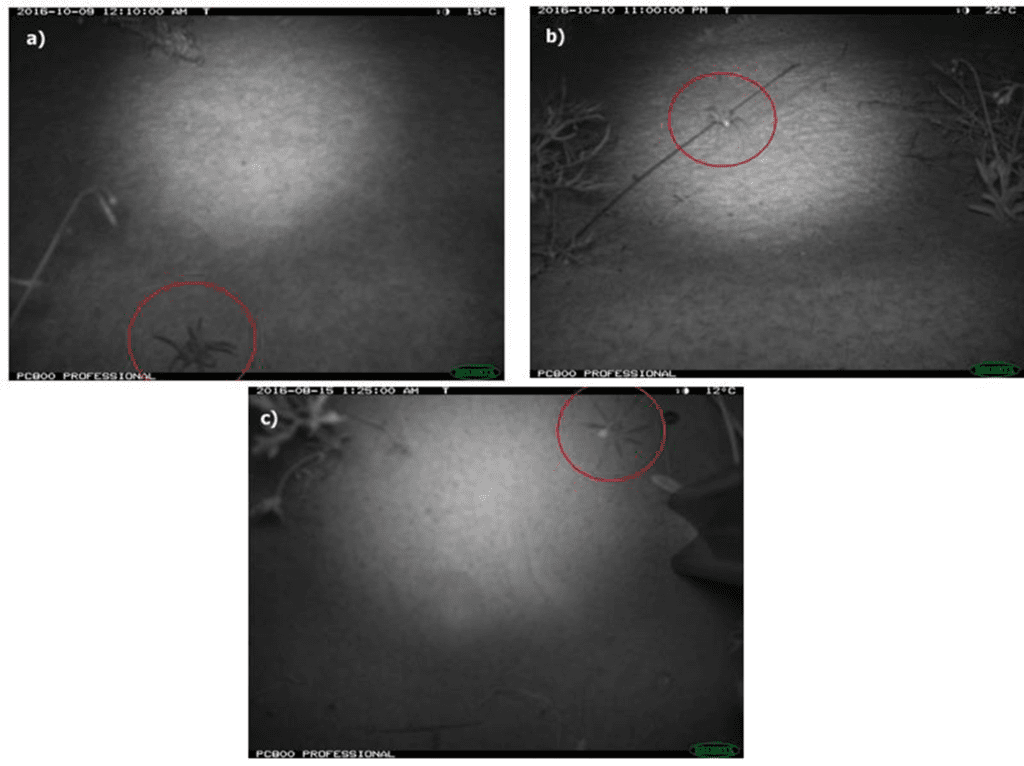

Compared to traditional sampling methods, camera traps provide numerous advantages. They are relatively non-invasive, collect information on numerous species, are convenient and cost-effective, they can monitor continuously over extended periods of time and be used at a range of spatial scales. Hence, their use in ecology has risen dramatically over the last few decades. However, few studies have used cameras to reliably detect fauna such as invertebrates or used cameras to examine specific aspects of invertebrate ecology.

“Our previous research exploring the interaction between wolf spiders (Lycosidae: Lycosa spp.) and the lesser hairy-footed dunnart (Sminthopsis youngsoni) in the north-eastern Simpson Desert, Queensland, found that camera traps provided a viable method for examining temporal activity patterns and interactions between these species. Using the information collected from these cameras, we further examined whether these patterns in wolf spider activity varied under different environmental conditions. Specifically, between burnt and unburnt habitats and the crests and bases of sand dunes. We also explored whether cameras were able to detect other invertebrate fauna.”

Tamara Potter, TERN Ecosystem Surveillance Project Officer

Camera traps reveal secrets of a complex desert ecosystem

Twenty-four cameras were deployed over a 3-month period and 2,356 confirmed images of 7 invertebrate taxa were captured, including 155 time-lapse images of wolf spiders. Overall, no clear difference was found in nightly activity with respect to dune position or fire history, but twice as many wolf spiders were detected in unburnt compared to burnt areas. This behaviour may be related to predator and prey dynamics – that is, preferring areas with more vegetation cover for protection from predators (such as the lesser hairy-footed dunnart) or favouring these unburnt areas as camera data revealed the spiders also had a greater availability of prey species.

“Despite some limitations, including the reliance on time-lapse imagery and therefore the huge number of images obtained, camera traps appear to have considerable utility as a tool for determining activity patterns and habitat use of larger arthropods such as wolf spiders. If camera technology continues to improve, the application of cameras as a cost-effective, non-invasive tool to study invertebrates, particularly those of conservation interest, would be invaluable.”

Tamara Potter, TERN Ecosystem Surveillance Project Officer

Camera traps allow detailed research into general invertebrate behaviour and biology, as well as enable a greater understanding of the role of invertebrates in terrestrial ecosystems. They can also give insight into trophic interactions and community-level processes, help inform us as to how invertebrates may be impacted by environmental fluctuations such as climate change and, more broadly, could be applied in the study of landscape health and function, as invertebrates are often used as indicators of habitat restoration and rehabilitation.

For more information

- Data from this project is available via the TERN data portal

- Potter TI, Greenville AC, Dickman CR. 2018. Assessing the potential for intraguild predation among taxonomically disparate micro-carnivores: marsupials and arthropods. Royal Society Open Science 5:171872 DOI 10.1098/rsos.171872.

- Potter TI, Greenville AC, Dickman CR. 2021. Night of the hunter: using cameras to quantify nocturnal activity in desert spiders. PeerJ. 9, e10684. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10684.

- WildObs Australia – transforming Australian vertebrate research by producing a digital Wildlife Observatory through Camera trapping

- TERN 7 September 2022 Webinar: Technology for conservation - traces of biodiversity