International ecosystem research networks have been closely evaluating TERN infrastructure as recent collaborative information sharing exercises in China and Chile strengthen ties with partners from all corners of the globe.

|

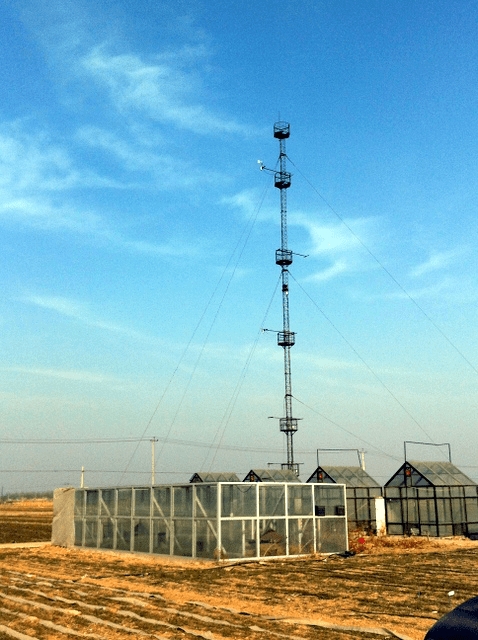

An instrument tower and other research facilities at CERN’s Luancheng Agro-Ecosystem experimental station in Hebei Province – one of CERN’s 42 field research stations for various ecosystems, including agriculture, forestry, grassland and water bodies |

Collaboration is at the heart of what we do here at TERN – across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, locally, regionally, nationally, internationally. Most of the ecosystem science problems we face are simply too big and too complex to deal with in any other way.

Our international collaborations allow us to present Australian ecosystem science to the world and advance Australia’s research standing globally. TERN took two more steps towards ensuring Australia plays a leading role in global ecosystem science with recent collaborative visits in China and Chile.

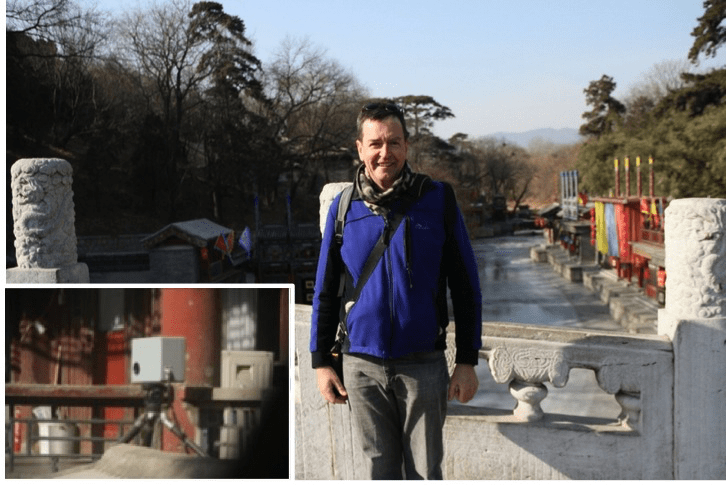

Last month Associate Professor Mike Liddell, the Director of our Australian SuperSite Network and Principal Investigator of the FNQ Rainforest SuperSite, made a visit to the Chinese Ecosystem Research Network (CERN), a long-standing partner of TERN.

Much of Mike’s time with CERN was spent talking about how TERN operates, finding out about how CERN operates – with a view to developing complimentary hard and soft infrastructure systems across the networks. Part of this included a presentation on TERN’s SuperSites at the China Ecological Forum hosted by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. TERN’s data collection, flow and delivery infrastructure was also highlighted during the discussions.

Mike had the opportunity to visit CERN’s Luancheng Agro-Ecosystem experimental station in Hebei Province – one of CERN’s 42 field research stations for various ecosystems, including agriculture, forestry, grassland and water bodies. He also visited a key observation site in the Chinese Phenology Observation Network at Beijing’s Summer Palace.

At the two field sites, Mike and his Chinese counterparts shared information on methods of ecosystem monitoring used in the two countries. They looked at the complex scientific studies that CERN undertakes in agricultural landscapes such as Luancheng and discussed TERN’s network of time-lapse cameras, known as PhenoCams, which are installed across the Australian SuperSite Network and are used to monitor vegetation phenology.

‘CERN’s Secretary General Professor Xiubo and the other CERN researchers were interested to hear how TERN facilities such as OzFlux, AusCover and eMAST are joining forces with ‘SuperSites’ to carry out scalable, process-based ecosystem monitoring,’ said Mike.

TERN’s Mike Liddell visits an observation site of the Chinese Phenology Observation Network in Beijing’s Summer Palace (main), which, like TERN, uses ‘phenocams’ (insert) to observe changes in the vegetation at the site over time (photos courtesy of Yu Liu)

|

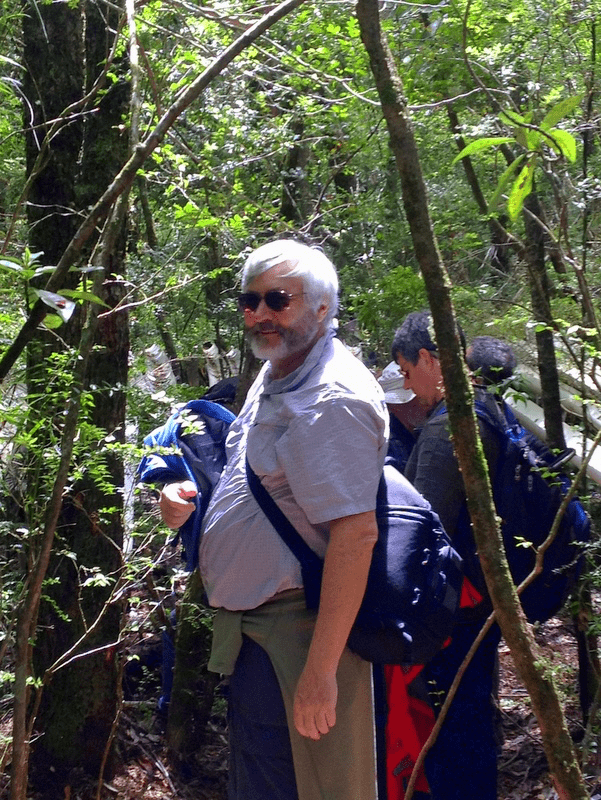

| TERN’s Director, Professor Tim Clancy, at Senda Darwin Biological Research Station in Chile during an information sharing trip to present TERN’s ecosystem science approach at the 22nd International Long-Term Ecological Research Network (ILTER) Meeting in December 2014 |

From China all the way to southern Chile’s stunning Chiloé Island, where TERN’s Director, Professor Tim Clancy, and Partnerships Director, Associate Professor Nikki Thurgate, recently attended the 22nd International Long-Term Ecological Research Network (ILTER) Meeting alongside 27 other international member networks.

‘The meeting program was packed with fascinating reports from member networks and provided and opportunity for discussion of global projects including all the projects using TERN,’ says Nikki.

In a sign of TERN’s position as a role model in the international ecological research community, Tim was asked to give an overview presentation on TERN from build to operation. This invited talk was an opportunity for other member networks to see the work of TERN and importantly to understand how the integrated nature of TERN is crucial to better understanding our global environments.

The current chair of ILTER, Dr Manuel Maass of Mexico, echoed these sentiments in saying that ‘TERN is a very good example of what ILTER is about and where it needs to go.’

Professor Martin Forsius of the Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) was even more enthusiastic saying ‘The TERN concept is the future for ecosystem science. That is how we should study problems on relative scales from local to global. TERN and similar projects such as China’s CERN, are good models for the European Union and we should move in that direction.’

One of the key topics of discussion at the Chile meeting was the importance of forming lasting and meaningful partnerships to tackle global environmental problems. It was recognised that without these in place geographic and institutional barriers can be insurmountable to collaboration.

‘One of the key learnings that TERN offers the international community is that partnerships need to be based on a mutual willingness to share data, codes, products and information’ says Nikki.

‘The ecosystem science community has recognised this need as evidenced by the proliferation of similar networks to TERN, rather than individuals working in isolation.’

In yet another recent example of the spirit of sharing with the international community, TERN’s Eco-Informatics facility is now working with ILTER to host their website.

Opportunities exist for all parts of TERN to be involved in ILTER as the breadth of global research encapsulated under their umbrella extends into all areas of ecosystem science.

- For more information please contact Nikki.thurgate@adelaide.edu.au and check out the ILTER website.

Published in TERN newsletter February 2015