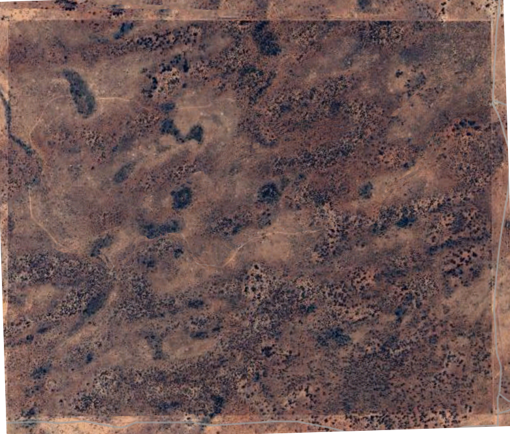

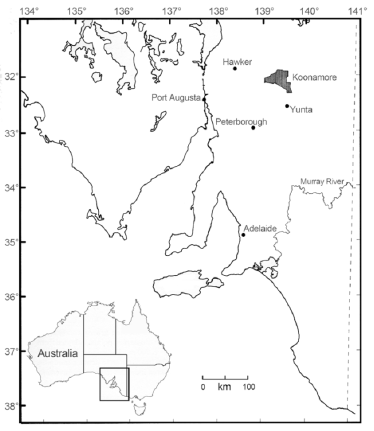

In the harsh, sun-baked country 400 kilometres north-east of Adelaide, something remarkable has been quietly unfolding for nearly a century. Behind a simple fence on Koonamore Station lies one of Australia’s most extraordinary ecological experiments – and one of the world’s longest-running monitoring sites for rangeland recovery.

The story begins in 1925, when Professor Theodore George Bentley Osborn from the University of Adelaide cast a critical eye over South Australia’s battered semi-arid rangelands. What he saw wasn’t pretty – vegetation hammered by decades of sheep and rabbit grazing, the landscape stripped bare. But Osborn had vision. He convinced the owners of Koonamore Station to fence off 390 hectares of their most degraded country, not for grazing, but for science.

“Let’s see what happens when we give the bush a chance to bounce back,” was essentially Osborn’s proposition. It became formally known as the TGB Osborn Vegetation Reserve in his honour, and 90-years of mostly continuous monitoring and data collection at the site have captured a complete history of the site’s vegetation.

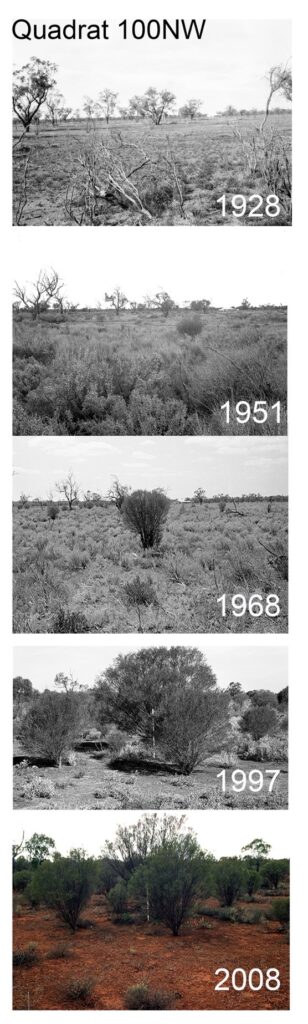

The results have been nothing short of spectacular. What started as bare, trampled earth began its slow transformation almost immediately. Mulga (Acacia aneura) started creeping back across the sand dunes, blackoak (Casuarina pauper) reclaimed the plains, and the distinctive chenopod shrublands – those silvery-grey saltbushes and bluebushes that define much of Australia’s arid interior – gradually returned.

But this wasn’t just about watching plants grow back. From day one, Osborn and his team established permanent quadrats (square monitoring plots) and photopoints throughout the reserve, creating what would become an unparalleled scientific record.

Photopoint, 18 June 1930

There are more than 6,000 photographs now available via TERN’s Data Discovery Portal, such as before and after shots taken in 1926 and 2008, that enable sophisticated species analyses and show how vegetation has changed in the absence of grazing.

The dedication required to maintain this project has been extraordinary. Generation after generation of researchers, students, and volunteers have trekked out to this remote site, diligently retaking the same photographs from the same spots, re-measuring the same plants, and recording the same transects. The exceptionally diverse set of population-related observations totalling almost 250,000 records represents one of the most comprehensive datasets on arid ecosystem recovery anywhere in the world.

The late Dr Russ Sinclair, who oversaw much of the recent work at the reserve, noted the site’s peaceful, almost cathedral-like quality – a stark contrast to the surrounding grazed country. The boundary fence creates a dramatic divide: on one side, the original degraded rangeland still struggling under grazing pressure; on the other, a thriving ecosystem that demonstrates the remarkable resilience of Australian native vegetation.

The research has had global significance. Koonamore was instrumental in facilitating research during the UNESCO Arid Zone Research Program and in the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program on Global Warming. The findings have fundamentally shaped our understanding of how arid ecosystems function and recover, influencing rangeland management practices not just across Australia’s vast drylands – which cover 81% of the continent – but in similar environments worldwide.

The timing couldn’t be more critical. With intensifying pressure on Australia’s rangelands, and pastoralism generating billions in economic value annually, understanding how these fragile ecosystems respond to different management approaches is essential. Koonamore provides the baseline data that enables scientists to separate the effects of grazing from climate variability – something impossible with short-term studies.

As Associate Professor José M. Facelli from the University of Adelaide explains, this long-term data is “helping answer important questions about the ecology of arid zone vegetation and the impacts grazing and climate change have on arid ecosystem functions” – questions that can only be answered through decades of patient observation.

Today, all this invaluable data is freely available through TERN’s Data Discovery Portal, ensuring that nearly a century of careful observation continues to benefit researchers worldwide. The Koonamore story isn’t just about one fenced paddock in remote South Australia – it’s a testament to the power of long-term thinking and the remarkable ability of Australian landscapes to heal when given half a chance.

About the data: records of the different measurements and observations of the reserve obtained from the original recording sheets at the University of Adelaide were entered into TERN in 2008–2014 by Dr Russ Sinclair (who died in 2023). In the Koonamore tradition of extraordinary dedication, the data currently available has been cleaned and revised by TERN’s Dr Alison Specht to ensure the data are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. Each category of data has at least one spreadsheet (.csv), a data dictionary (.csv) for each spreadsheet, and a metadata file explaining the content of the file(s). With the exception of undocumented photographs, no data other than those supplied by Dr Sinclair in 2014 are available digitally at present.