TERN’s National Ecosystem Assessment System for Australia (NEASA) project is creating a national framework that provides consistent criteria and nomenclature for assessing ecosystem status and trajectories, as well as a means for measuring the impact of restoration initiatives. Central to this effort is the development of State and Transition Models. But how exactly do they work and why are they important for ensuring long term investment in nature positive initiatives?

With its myriad landscapes and a continent spanning several climate zones, Australia is home to an enormous amount of ecosystem diversity: from tropical rainforests to arid deserts to the Australian Alps. It’s clear that the monsoon vine thickets lining the Kimberley coast are not interchangeable with the eucalypt forests deep within Tasmania’s Tarkine, but if you look closely, there is also profound diversity to be found within a single ecosystem type. Take for example, Australia’s iconic mulga lands.

Around 20% of the Australian continent is covered by a patchwork of acacia woodlands and shrublands, which are dominated by Acacia aneura and its close relatives, collectively called ‘mulga’. Mulga are long lived, hardy, and exceptionally well-adapted to the hot, arid conditions of Australia’s inland regions thanks to long taproots that delve up to 3 metres to access water. Instead of leaves, mulga possess narrow, flattened stems called phyllodes that help conserve that water, and which are angled upright to avoid the intense midday sun. Due to this unique hydrological talent, where there is mulga there is biodiversity.

Mulga are crucial to the ecosystems they inhabit, acting simultaneously as foundation species and keystone species by providing ecosystem structure while also supporting diverse flora and fauna. They enrich soil while mitigating erosion. They offer shade, nutrients, and even secondary hydration in the form of dropped phyllodes. Where mulga thrive, they provide a robust habitat for understory shrubs, forbs and grasses and native wildlife.

There is a great deal of phenotypic variety between and within mulga populations and the ecosystems they support. In addition to differences in individual mulga species and varieties, there are differences in location and local environments. In harsh conditions, mulga grow as short, dense, bushy shrubs, but where more water is available, they grow taller and more tree-like. In Western Australia alone, mulga rangelands comprise both shrublands and woodlands that cover an area of more than 9.5 million hectares, spanning a wide variety of soils, geology, elevation, slope and hydrology. There are mulga ecosystems in stony uplands and rocky slopes, on hardpan plains, on the fringes of salt lakes, and in river flood plains. The associated flora and fauna vary accordingly: from foliose lichens to spinifex and berry bushes; from vulnerable crest tailed mulgaras to critically endangered mallee fowls and great desert skinks. These mulga ecosystems not only differ from each other, they also often differ from what they once were.

Since the arrival of Europeans, large areas of mulga ecosystems have been modified by livestock grazing, or have been fragmented by mining activities, infrastructure development or roads. Introduced species –from feral herbivores to invasive weeds – have caused profound changes in vegetation and soil conditions. In other words, mulga ecosystems have been modified to different extents and in a variety of different ways.

Restoring Diverse Places

Mulga rangelands join a long list of Australian ecosystems requiring restoration and conservation. The success of such efforts relies on long-term, investment from governments, industry, and communities. But attracting and maintaining finance requires a clearer understanding of where we are now, what we aim to achieve, and how we plan to get there, says Dr Alison O’Donnell, a senior research scientist at CSIRO. She notes that this is particularly salient for biodiversity credit markets, such as the Nature Repair Market, that incentivise nature-positive land management practices and which rely on an ability to consistently assess and compare the impacts of restoration interventions. But this is tricky, precisely because biodiversity is so diverse.

“Different ecosystems have different drivers and different tipping points, so it’s been challenging to compare them,” says Alison.

Australia needs a way to map, monitor and predict trajectories of its natural and modified ecosystems at regional and national scales, in a consistent and repeatable way. Through its National Ecosystem Assessment System for Australia (NEASA), TERN is developing infrastructure and tools towards this goal.

The NEASA project is supported by TERN and is led by Dr Suzanne Prober, Dr Anna Richards, Dr Kristen Williams, and Dr Alison O’Donnell at CSIRO. The NEASA team is working in collaboration with DCCEEW and over 50 ecological scientists, restoration practitioners and environmental policy makers around Australia to develop generalised templates and guidance for describing ecosystem condition in a consistent and transparent way across Australian ecosystems.

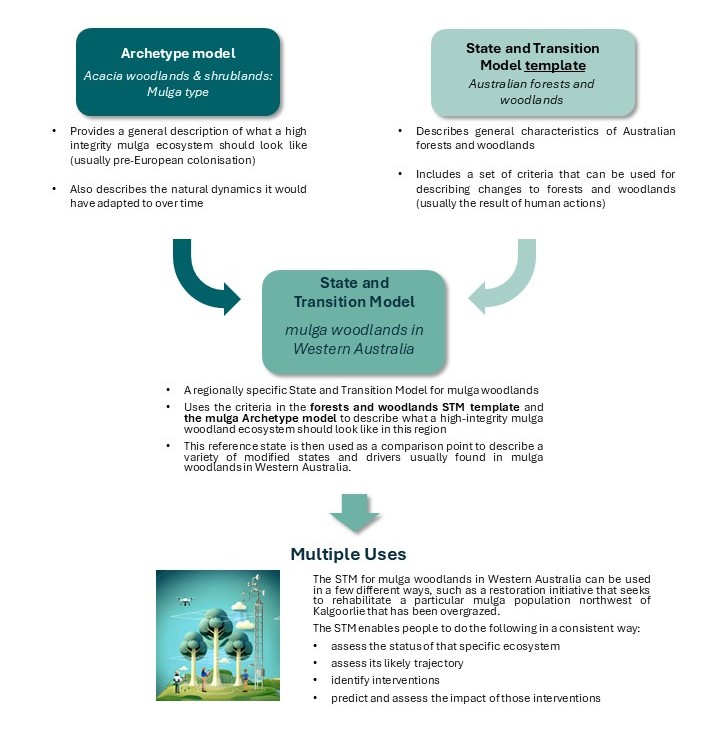

The first phase of NEASA involves the development of ‘Archetype models’ for Australian ecosystem types (describing the natural dynamics of Australian ecosystems), as well as the development of generalised ‘State and Transition model’ templates for each of three broad structural categories of ecosystems.

Archetype models

To develop the archetype models of Australia’s ecosystems, NEASA builds on prior work [Australian Ecosystem Models Framework], explains Alison. “We begin by describing the highest integrity example of that ecosystem,” she says, but clarifies that NEASA does not map a particular existing ecosystem. It’s not that prescriptive. The aim is to simply describe what a high integrity version of this ecosystem would look like, as well as the natural dynamics it would have adapted to over evolutionary timeframes, from seasonal changes to Indigenous burning practices. She explains that the Archetype model of an ecosystem describes how that ecosystem would have appeared and functioned prior to European colonisation.

NEASA has developed more than 45 Archetype models so far, describing ecosystems as diverse as rainforests, mangroves, eucalypt forests and woodlands, hummock grasslands and freshwater wetlands. Each one is generic and broad enough to be useful at a national level. For example, the mulga Archetype model must be broad enough to apply to the large diversity of mulga shrublands across Australia. In addition, each Archetype model must have enough flexibility to be useful at a regional or local level.

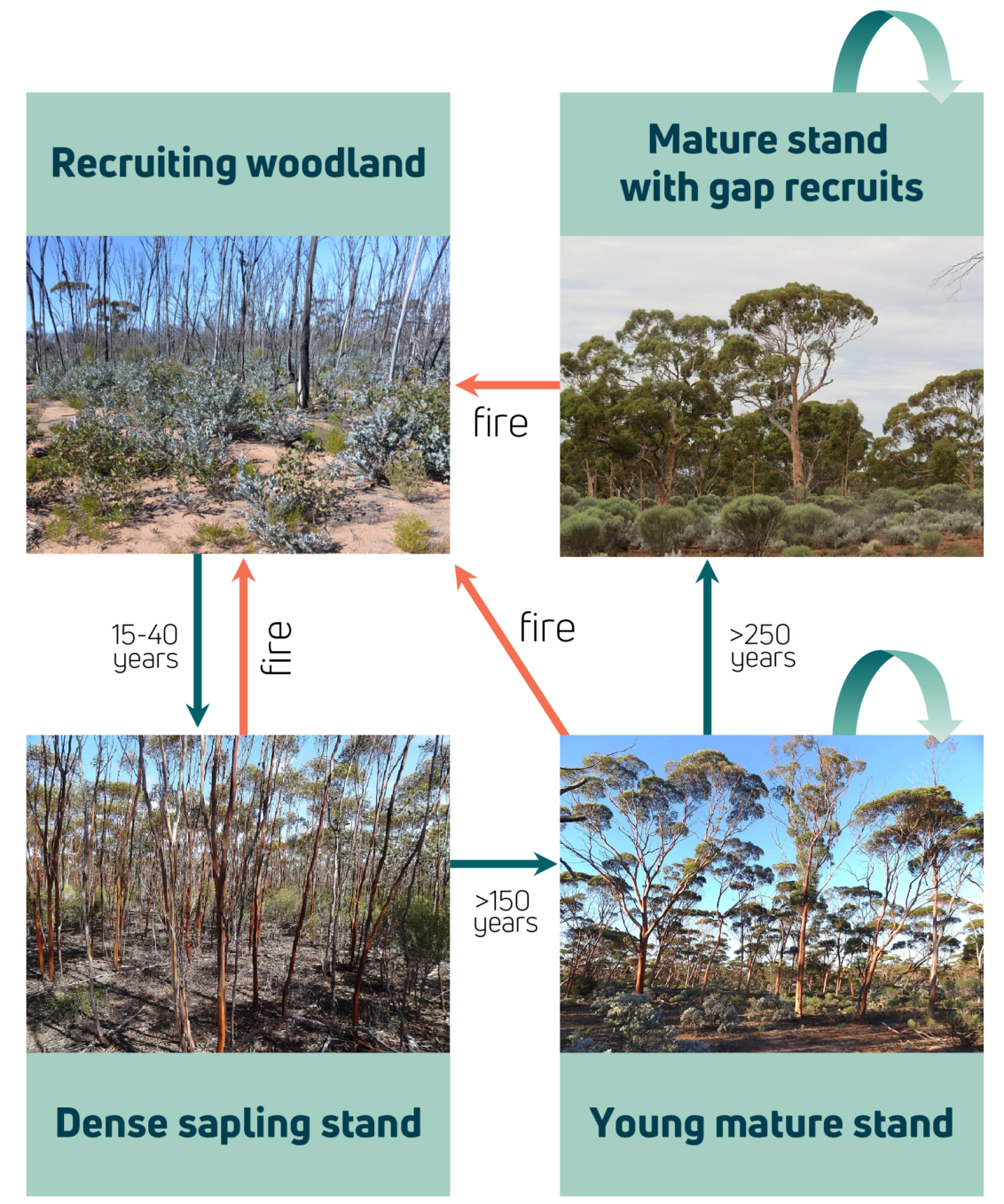

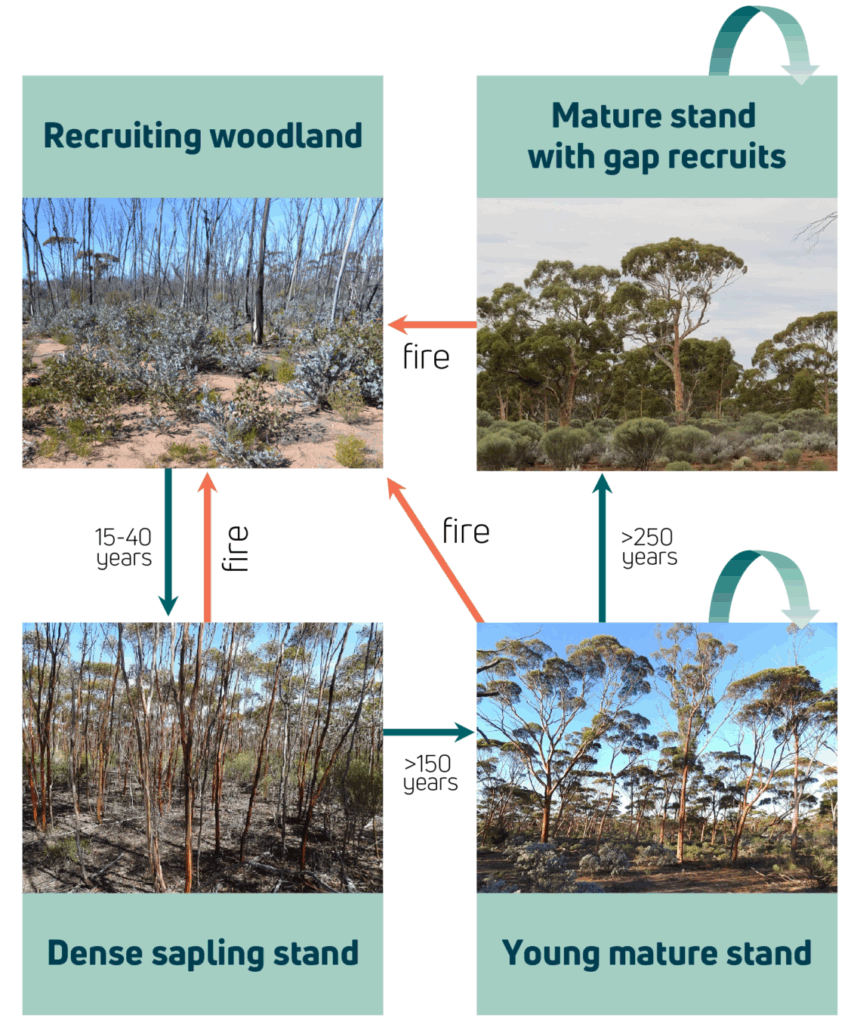

Figure (right): A simplified archetype model for obligate-seeder eucalypt woodland, with images for each expression (modified from Prober et al 2023; Gosper et al 2018) SM Prober

State and Transition Model templates

The next step involves State and Transition models (STMs), which are flexible tools that can be used to describe and communicate characteristics of Australian ecosystems and how they change in response to different drivers. But because they are flexible, STMs can end up looking quite different depending on who builds them and for which ecosystem, which makes them hard to compare.

That’s where TERN’s NEASA initiative comes in. In partnership with the Department of Climate Change, Energy and the Environment, NEASA is developing STM templates to guide the consistent development of STMs across Australian ecosystems. These templates cover three broad structural ecosystem types: forests and woodlands, shrublands, and grasslands. Each template outlines all the plausible ecosystem states, including reference and modified states, as well as the transitions that can occur between them.

“The templates are intended to be used as a ‘palette’ of plausible states and transitions that STM developers can choose from,” says Alison. “They can then ‘downscale’ with more specific detail for their region of ecosystem type of interest.”

“They also facilitate more consistent allocation of ecosystem condition scores, which is critical for national-scale nature repair programs.”

State and Transition models can be quite simple and conceptual or more complex and detailed, she explains.

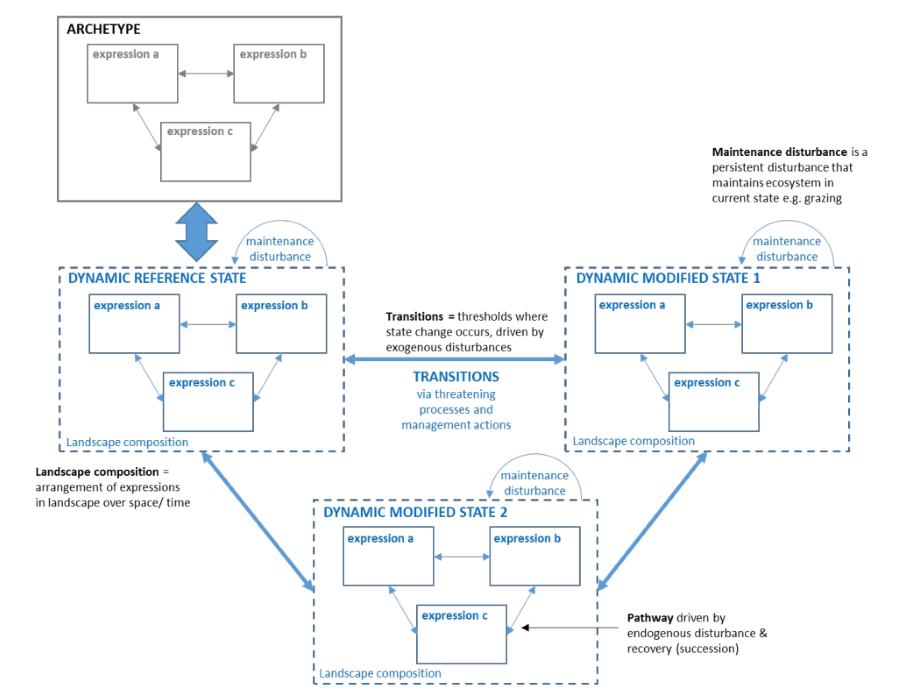

In their simplest form, they can be represented as box and arrow diagrams, where each box represents the state of an ecosystem. The first box is usually the ‘reference state’. For this, the NEASA team uses the appropriate Archetype model as a guide to identify criteria for a high-integrity state of an ecosystem type.

The remaining boxes represent modified states of that ecosystem. The general structure, function and condition of each of the modified states are described in terms of their departure from that reference state.

Components of a State and Transition Model

A reference state: the highest integrity example of that ecosystem

the reference state may have a few different temporary expressions

A series of modified states that are possible

the modified states are described by their departure from the reference state

each modified state may have a few different temporary expressions

Transitions: the external drivers that can shift an ecosystem from one state to another

“This is where ecological data are critical,” says Alison. Observational data, such as that provided via TERN’s Data Discovery Portal, enable the NEASA team to identify reference ecosystems and develop descriptions of the different types of modified states and their dynamics.

The arrows between the boxes indicate how an ecosystem can transition from one state to another.

“A state, even a highly modified one, is relatively stable unless acted upon by an external driver,” says Alison.

“Natural drivers of change usually only cause temporary fluctuations or ‘expressions’ that change the way an ecosystem looks for a while, but it returns to baseline over time.”

“Bigger drivers of change in an ecosystem – the ones that completely bump it from one state to another, often for the worse – usually come from humans.”

Example: mulga woodlands

A National-Scale Framework

Through Archetype models and STM templates, NEASA is creating a national scale framework that provides consistent criteria and nomenclature for describing ecosystem status and trajectory, as well as a foundation for measuring the impact of restoration initiatives.

The STM templates developed in the TERN NEASA initiative have been used to develop 17 regional-scale STMs so far, in partnership with other organisations. This includes the recently published State and Transition Models for Western Australian Mulga Rangelands, which describes regionally-specific STMs for mulga woodlands and shrublands. Many regional STMs are being developed through the Ecological Knowledge System to support the Nature Repair Market. They can be used to inform local to regional land use planning decisions and can help guide the development of national and international restoration and conservation policies and reports.

‘We’ve achieved a lot already,” says Alison, “A key next step is establishing the data infrastructure to host and share these models and templates so they can be reliably accessed and used across Australia.”