Growling grass frog credit: Geoff Heard

Understanding long-term population changes in Australia’s threatened and near-threatened species is crucial for monitoring progress towards national conservation targets. “It’s fundamental to helping us conserve Australia’s biodiversity,” says Tayla Lawrie, Project Manager for the Threatened Species Index.

“Having information on long-term population trends is critical to the justification, design, and evaluation of targeted conservation actions for any threatened species,” she explains.

“Without up-to-date and robust estimates of population change, it’s impossible to gauge the success of conservation policies, nor measure the benefits of conservation investments or justify further targeted responses.”

But monitoring and reporting population trends at a national level are challenging because most data on species abundance are collected via individual projects that monitor specific ecosystems or specific species. Indeed, for decades hundreds of threatened species have been monitored across Australia by dozens of different government, non-government, and community groups, and even by private individuals and landholders. Each collecting data at different locations, using a wide variety of data collection methods and across different time frames. It can be difficult to get a clear picture.

The Threatened Species Index

Australia’s Threatened Species Index (TSX) is a continental-scale database of thousands of threatened species monitoring projects from across Australia. Often likened to a “health index” for ecosystems, the TSX is widely recognised as a key metric for tracking and reporting on changes in Australia’s threatened and near-threatened species at national, state, and regional levels.

Development of the TSX began in 2016 and was initially funded and managed by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program (NESP) Threatened Species Recovery Hub. In 2018, the first release of the TSX, the Threatened Bird Index, focused on long-term trends in populations of threatened and near-threatened birds. This was soon followed by a Threatened Mammal Index in 2019 and the Threatened Plant Index in 2020. When funding for NESP finished in 2021, TERN became the new custodian of the TSX ensuring the ongoing provision of the database and its services. A major update to the Threatened Bird Index was published in 2023, followed by a new Threatened Frog Index in 2024. The most recent addition – the Threatened Reptile Index – has just been published.

Altogether, the TSX contains over 25,000 data sets collected by hundreds of organisations, scientists and citizen scientists who have been monitoring populations of 395 threatened and near-threatened mammals, birds, plants, frogs, and reptiles across Australia and uses these data to estimate abundance trends using the Living Planet Index method.

A Collaborative Approach

The TSX serves a wide range of users, including researchers, NGOs, and government agencies, each with distinct objectives. Some may want to use TSX data to answer specific questions in applied ecology, others may want to use TSX data to guide field research activities, while others want to understand long-term trends in threatened biodiversity and use this information to shape policies and conservation programs. Gaining a clear understanding of precisely how people use, or want to use, the TSX is essential to strengthen its capabilities and ensuring it remains valuable for years to come.

With this in mind, the TSX recently hosted a workshop in collaboration with the University of Queensland’s Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science which brought together a cohort of TSX users to exchange ideas for improving the use of the TSX dataset in research and conservation.

The workshop, titled Tapping the research potential of the national Threatened Species Index, was held at the University of Queensland’s Long Pocket Precinct, and served as an interactive forum for TSX users to share their experiences using TSX data in research, hear about the current research needs in this space, and to identify opportunities to broaden its functionality. The workshop also involved discussions on how to increase the impact of TSX data on policy and conservation.

In addition to updates from the TSX team, the workshop included several invited talks from researchers and representatives from the University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology, as well as NGOs including The Australian Wildlife Conservancy and the World Wide Fund for Nature Australia.

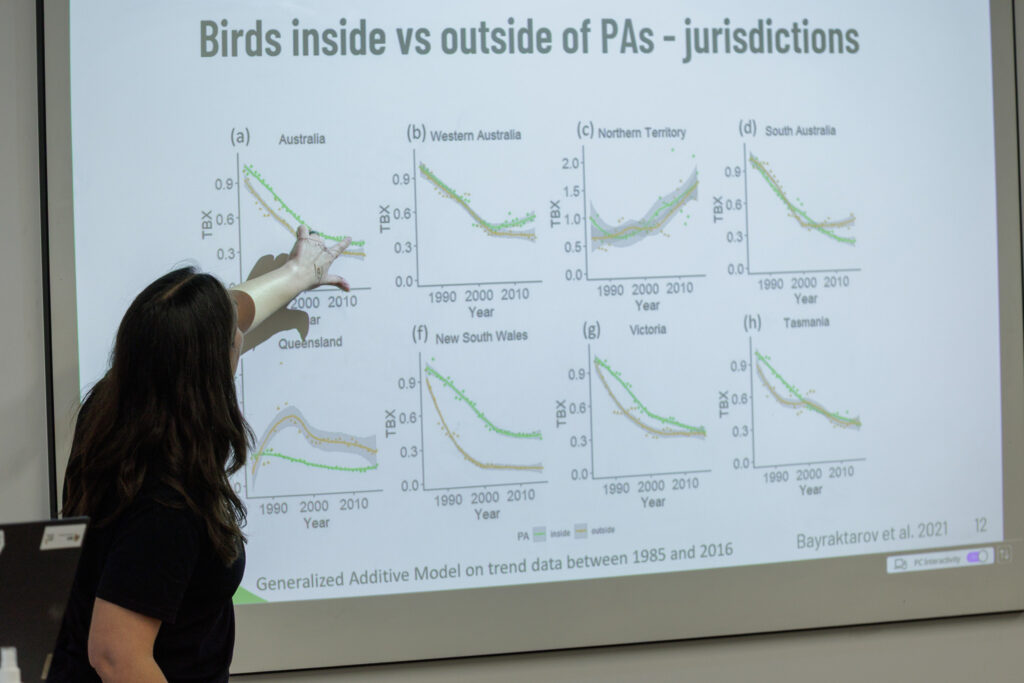

The talks provided overviews of current research and conservation programs, highlighting their most pressing questions and data needs. Several fascinating case studies were also presented, highlighting how TSX data have informed specific investigations: assessing the impact of protected areas on threatened bird trends, examining how management strategies such as predator control influence threatened mammal trends, and understanding how protection and management together shape trends in Australia’s threatened plants.

There was also a focus on threatened species initiatives run by government agencies, as well as presentations on how TSX data are used in reporting and policy development. Speakers included representatives from Queensland’s DETSI Threatened Species Program, as well as Threatened Species Commissioner Dr Fiona Fraser who joined the workshop remotely from Canberra to highlight the crucial role TSX data plays in environmental reporting and policy development at the federal level. “It underpins a huge amount of work we do,” she said.

Through group discussions and break-out sessions, workshop attendees identified a number of research questions they believe the TSX could help address. This included questions that would either benefit from current TSX data or could guide future TSX activities to ensure the necessary data are available in the near future.

“The attendees were highly engaged and because of this we had a number of great outcomes from the workshop,” said TSX Science Advisor Dr Geoff Heard.

More than 30 research questions were identified from which several key themes emerged, including the use of TSX data to assess regional differences in population trends, to prioritise species requiring urgent conservation, and to better utilise the broader TERN datasets to understand threatened species trends. There was a robust exchange of ideas around the current challenges in data collection and analysis and how best to address them. Discussions covered how to identify and account for monitoring biases and also how we might maximise our understanding of species trends by combing the robust TSX time-series data with less structured occurrence data, like those from ALA or iNaturalist. Attendees also explored the challenge of sharing sufficient information about critically endangered populations to support research and conservation efforts, without revealing sensitive locations that might put them at risk.

Follow-up meetings are planned for early 2026 to prioritise and further develop some of these ideas, says Tayla. “This research will strengthen collaborations between academia, government, NGOs and TERN, and ensure that the data we collate, analyse and share have the greatest possible impact on the species we care about.”