Wayne Meyer has always been interested in water: how it moves through natural and agricultural systems, and by what happens to landscapes when there isn’t enough to go around. He spent 27 years at CSIRO as an irrigation scientist, systems modeller and sustainable agriculture research manager, and was the founding CEO of the CRC for Irrigation Futures, where he worked on large-scale irrigation projects across the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB). He wanted a better understanding of the vast and vital water-system of the MDB, as well as its capacity for resilience. Curiously, he decided to search for answers in an ecosystem that has evolved to survive on very little water. His work in establishing and managing the TERN SuperSite at Calperum Station in the Mallee country of South Australia’s drylands has led to the generation of valuable long-term multiscale time series data. This is shedding light on critical relationships between energy, carbon, nutrient stocks and water in the lower MDB and revealing clues to both its past and its future.

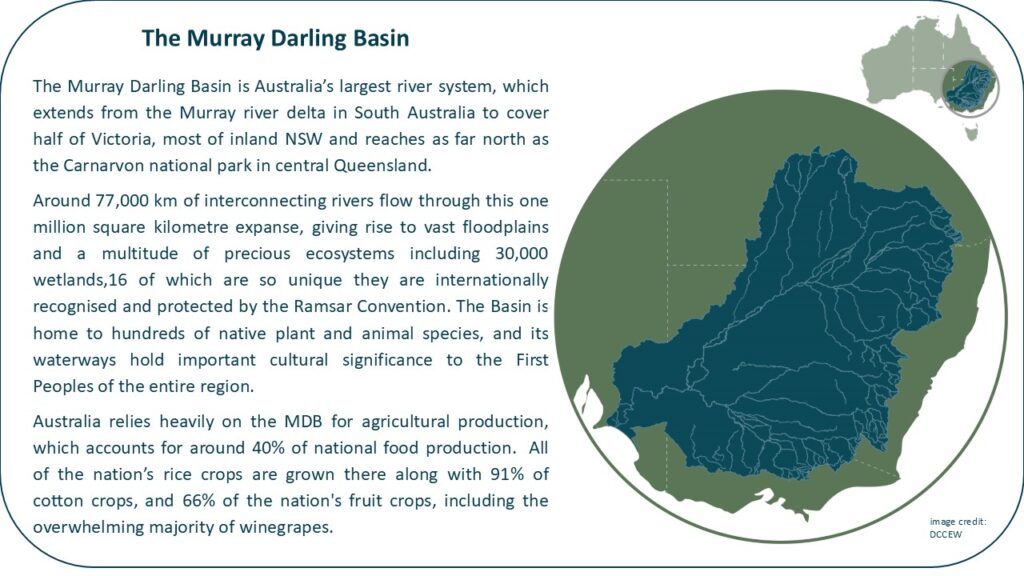

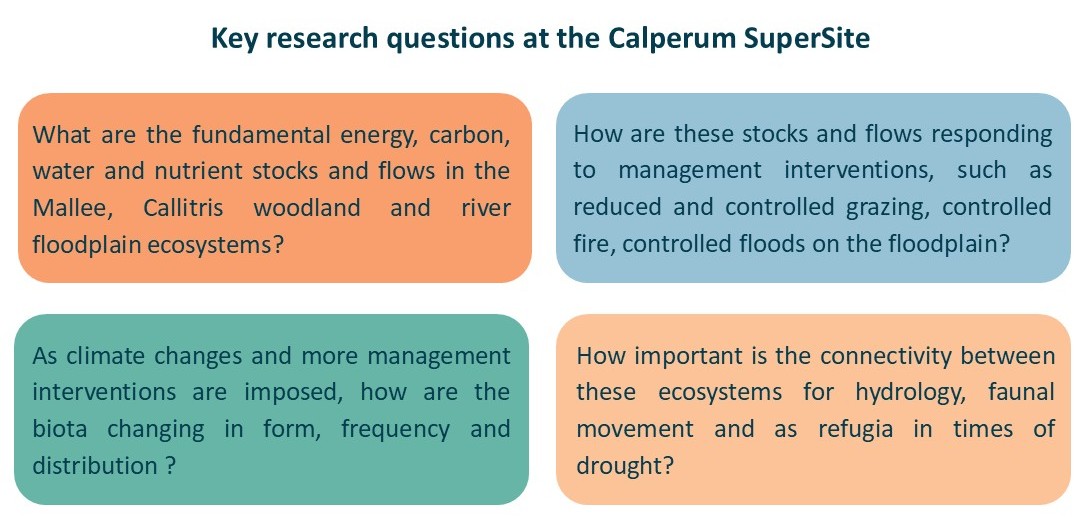

The Murray Darling Basin (MDB) is an enormous, ecologically and culturally important network of rivers and interconnected ecosystems, a source of drinking water for millions and Australia’s primary food bowl. It is also slowly drying out. Currently there is a high opportunity cost associated with agricultural water use in the MDB, says Wayne. Water used in irrigation is diverted from rivers and surrounding riverine and wetland ecosystems. It can no longer form a part of Indigenous cultural traditions. As the population grows and as the region becomes warmer and drier, more pressure is being placed on a system already under strain. Yet the complete hydrological cycle of this complex system is still not fully understood.

Wayne knew that you can’t solve the water problem by only looking at water. He was interested in all the processes that surround it, especially vegetation systems because they have a strong influence on soil stability, the carbon cycle and the water cycle, even in landscapes as seemingly sparse as Australian drylands.

“The vegetation determines the amount of carbon going into the system and the turnover in the soils that cover the land,” he says.

“As soon as you change the vegetation, everything changes. It changes the hydrology, and the evaporation rate. It changes the carbon and soil erosion, all that kind of stuff.”

If you want to understand the hydrogeology of an area, he says, you need to understand its vegetation.

Mallee Country

A significant amount of the lower MDB is covered by Mallee vegetation, which Wayne describes as “uniquely Australian”. Mallee is dominated by hardy, eucalypt species well-adapted to semi-arid conditions and calcareous soils. Although the high pH and poor water holding capacity makes calcareous soil extremely challenging for farming, Mallee eucalypts have adapted rather nicely. “That’s the interesting thing about Mallee,” says Wayne. “It’s perennial vegetation in a very low rainfall area. It’s got great survival mechanisms for both fire and drought.”

The key to this resilience is the ‘Mallee root’, a lignotuber that grows at the root crown, says Wayne, describing it as a woody swelling filled with starch, nutrients and dormant buds. The Mallee root enables each eucalypt to grow multiple trunks – a botanical gamble to ensure at least some of those trunks survive. Shallow roots fan out from the lignotuber, remaining close to the surface to collect whatever rainfall they can, while deep roots extend several metres underground to access stored sub soil water.

Wayne’s interest in Mallee goes all the way back to his childhood in South Australia where he was surrounded by a Mallee dominated landscape. “It’s where I come from, it’s where my country is,” he says. Yet despite its familiarity it also presented a puzzle.

In the early 2000s, when Wayne was already working on irrigation in the MDB, much was still unknown about how Mallee vegetation interacted with the water-cycle. At the same time, the Mallee system was itself changing due to rising temperatures, as well as grazing and land clearing in some places and recovery in others. But no one knew what impact these changes would have on the regional water-system. His search for answers led him to Calperum Station.

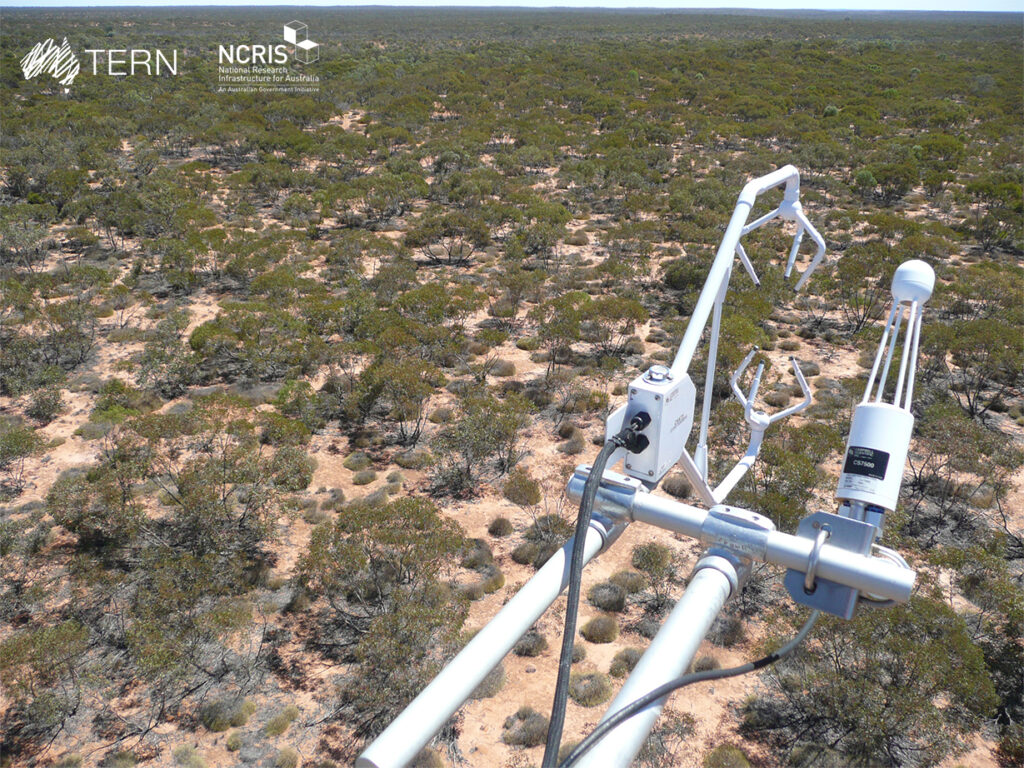

Left: Eucalyptus socialis is a Mallee tree species (image credit: Mark Marathon via Wikimedia Commons); Above: map of the Mallee woodlands and shrublands (in light blue) (image credit: DCCEEW); Below: view from the flux tower at Calperum looking out over the Mallee vegetation (image credit: Tim Lubke).

An ideal setup

Situated along the River Murray floodplains near Renmark in South Australia, Calperum Station spans 242,800 hectares and lies within the much larger Riverland Biosphere Reserve, a 9,000 km² protected landscape that contains the largest continuous stands of ancient Mallee woodland in the world. Calperum Station occupies a diverse section of this reserve and thanks to a gentle rise in elevation, the landscape covers three unique ecosystems from the creek-threaded wetlands at the river’s edge through the stands of Callitris pines fringing the floodplains up to the sparse Mallee woodlands on higher ground.

Historically, Calperum operated as a sheep station from the mid-1800s until 1994, when it was incorporated into the Commonwealth National Parks system. Since 2003, it has been managed by the Australian Landscape Trust (ALT). Native Title for the area is held by the First Peoples of the River Murray and Mallee.

With its vegetation, hydrology and land-use history, Calperum offered a rare opportunity to study connections and interdependencies associated with Mallee ecosystems. Wayne was also encouraged by Calperum’s protected status as well as the ALT’s active role in ecosystem rehabilitation and its support for research and education.

“It had all the right elements,” he says. “It’s really pretty impressive in terms of a stable place for gathering long term data and understanding the system that you’re in.”

“It’s an ideal setup.”

Clockwise from top left: Wayne at the acoustic sensor at Calperum; Tim Lubke climbing the tower; the eddy covariance flux tower from a distance; Wayne beginning one of many tower climbs, as Cacilia Ewenz provides safety support (Images provided by Wayne Meyer)

In 2010, Wayne and his colleagues were given the go ahead to establish the Calperum Mallee SuperSite as part of the NCRIS-enabled TERN project and with support from the ALT. The overarching aim was measuring the fundamental carbon, water, energy and nutrient pools and fluxes in South Australia’s iconic Mallee ecosystems, including how these are likely to change with climate and management. They began by erecting a 20-metre eddy covariance flux tower in the Mallee woodland and soon added phenocams, acoustic sensors as well as a series of probes to measure soil water content, temperature and electrical conductivity. Meanwhile, TERN-coordinated ecologists commenced intensive sampling across all the ecosystems across the site, characterising the vegetation and the soils. They received additional support from Dr Peter Cale, Chief Ecologist with ALT, who agreed to co-manage the site with Wayne and to provide data from bird surveys at Calperum. ALT also coordinated volunteers from the community to participate in vegetation and fauna surveys as well as restoration and maintenance work.

Once the Calperum SuperSite was fully established around 2012, the focus turned to making the incoming data and analyses openly available through TERN Data Discovery portal. In addition to helping to understand things like vegetation, hydrology and biodiversity changes in the riverland, the data generated at Calperum have also contributed to TERN’s CalVal program. The latter includes providing space agencies with access to Calperum sensor and survey data to validate satellite-derived remote sensing data across the continent. It also helps to validate modelled data products. An example of the latter is the accurate, high-resolution / high-frequency actual evapotranspiration (AET) data for Australia that are based on Earth Observation data validated against TERN flux data.

A major setback

It had taken a few years to find the site, secure funding and partnerships, purchase and set up equipment and then watch, happily, as the data began flowing. Wayne regularly made the three-hour trip from Adelaide to Calperum, visiting almost every month to ensure everything was running smoothly. He’d check equipment, climb the tower, make repairs when needed, and swap out data-rich SD cards for new ones.

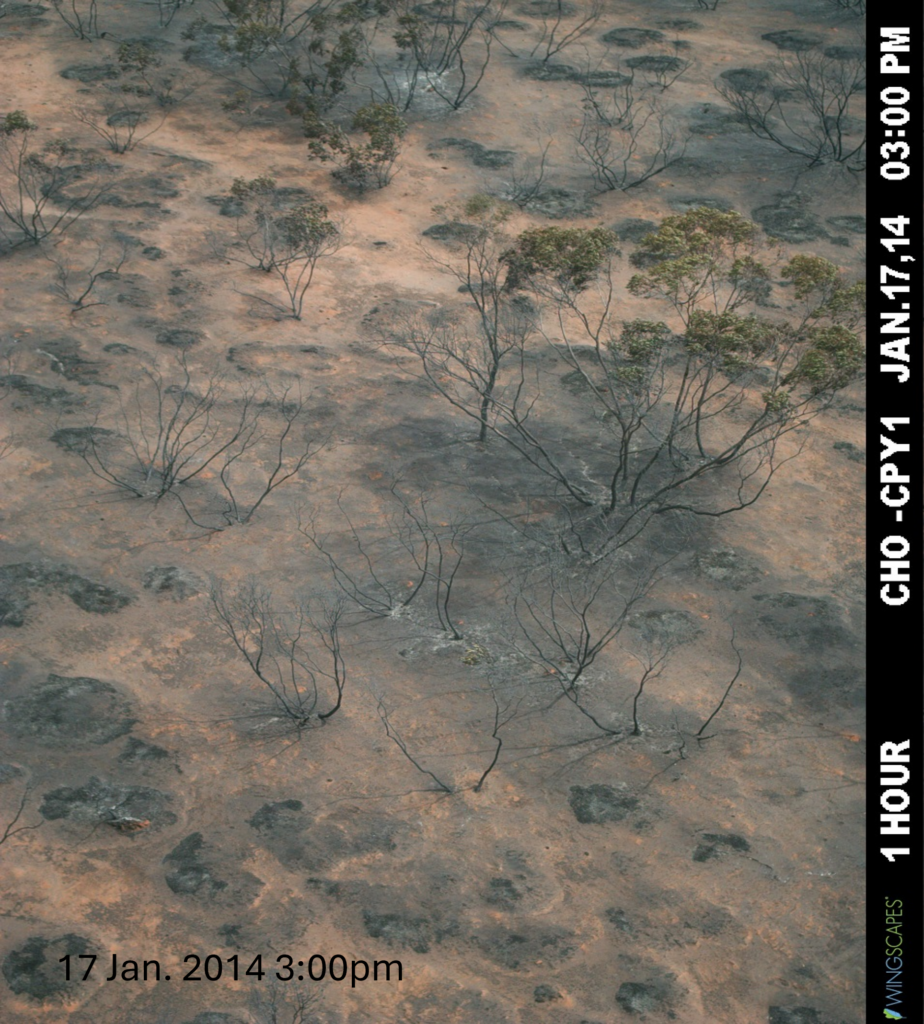

Then, in January 2014, one of his worst fears unfolded. He recalls hearing the news reports of a major bushfire in the Calperum area, the hideous sinking feeling that followed, all the phone calls and the agonising wait.

“We were monitoring the output from the flux tower and then you see, oh, it’s no longer reporting. But you’ve got to wait until you’re allowed to go in there and drive along the track and you just hope that the whole lot hasn’t been completely wiped out.”

When at last they were able to reach the site, they found a charred and desolate moonscape. As is common in Mallee country, the fire had burned intensely at ground level, fuelled by leaflitter and spinifex grass. Consequently, all the instruments lower than seven metres above the ground had been destroyed: temperature sensors, the soil water probes and all the cabling had burned; the infrared thermometer had melted; the solar panels had blistered; an acoustic sensor for recording birdsong was damaged beyond repair. Mercifully, the essential monitoring instruments and SD memory cards housed in a steel cabinet at the base of the flux tower were intact, as were instruments higher up on the flux tower.

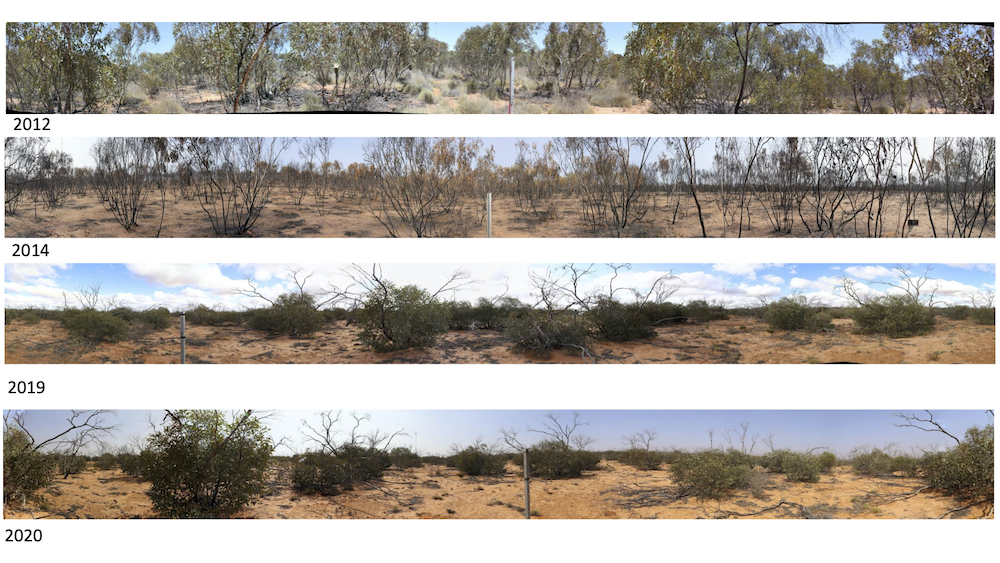

Left: image from phenocam at the top of the tower at 1pm on 17 Jan 2014, just prior to the fire passing through. Right: the last image from the phenocam at 3pm, as the fire passes through the area (phenocam images provided by Wayne Meyer). Below: panoramic time progression of Mallee vegetation at Calperum showing the impact of the fire and the slow recovery.

With help from members in the TERN-OzFlux community, Wayne and his colleagues from the ALT and the University of Adelaide were able to re-install instrumentation to get the site up and running again. While this was underway, they observed how the Mallee woodland was itself recovering.

For about a month, everything was black, Wayne recalls, just a layer of ash punctuated by blackened Mallee trunks, with dead crown leaves that the flames had never reached but managed to cook all the same. “But within about a month, all that ash and char was blown away and the leaves gradually fell off. So now you’ve got this kind of skeletal system sticking up in the air and within three months the lignotuber, the Mallee root, starts sending up shoots.”

Some of his students had been analysing soil respiration prior to the fire and then resumed their data collection soon after, says Wayne. “The fire didn’t affect soil respiration much at all, which is very surprising.”

In addition, he and his colleagues made an intriguing discovery about carbon conservation in Mallee woodlands. Forest fires often release a great deal of stored carbon into the atmosphere and it can take several years before the carbon storage capacity of a forest returns to baseline. This is certainly the case with temperate forests, such as coastal eucalypt woodlands. But data collected at the SuperSite showed Mallee behave quite differently. The Mallee woodland didn’t release very much stored carbon during the fire, says Wayne. Moreover, it returned to baseline carbon accumulation within just 2 years. “It’s a very carbon conservative system,” he explains. “It’s primarily because a lot of the carbon is actually stored by the Mallee trees in the dead, unburnt trunks and below ground in the lignotuber.”

‘Spider Cam’ : Wayne recalls the time that data coming in from infrared gas analyser at the top of the flux tower began getting progressively worse, which was strange because everything else was working properly.

“We couldn’t figure out what was wrong with it. We went out and had a look, couldn’t see anything. This went on for about two months.”

One day after climbing the 20-metre tower yet again, he discovered the problem. A tiny spider had been gradually building a small web in the corner of one of the mirrors, little by little obscuring the incoming light. Wayne evicted the unwitting interloper, and the infrared gas analyser was thereafter dubbed ‘spider cam’.

Mallee Critical Zone

It took about three months of hard work to get the SuperSite functional, but at last the data flowed again and regular management resumed. Still, Wayne knew that the site had even more to offer.

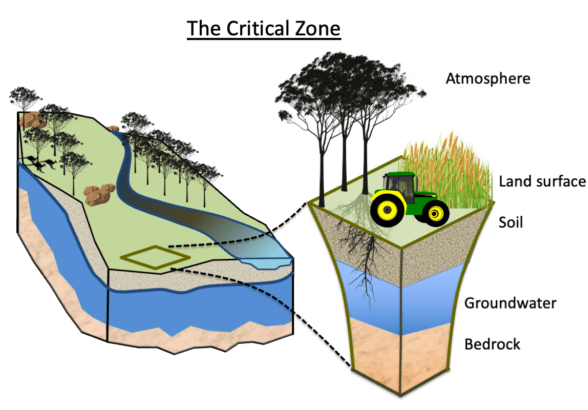

The Critical Zone is that zone that spans from groundwater (or bedrock) to the tops of the trees, and which sustains all life on the planet. The eddy covariance flux tower, soil monitors and other equipment at Calperum were providing valuable information about below and above ground processes, but to characterise the whole Critical Zone they needed more information about what was happening below ground, including how the Mallee trees were interacting with stored soil water and deep ground water.

To this end, and with funding from an ARC LIEF grant, the Calperum SuperSite gained an additional state-of-the-art, automated monitoring infrastructure to record stocks and flows of carbon, water, energy and biomass across the entire Critical Zone. Instrumented ground-water bores were installed to monitor groundwater fluctuations and water content. Water sampling and gas sampling instrumentation was also added to help track the interactions of the vegetation with the below ground environment. To this end, the team installed a Vadose-zone Monitoring System (VMS), developed by Sensoil, which helps scientists keep an eye on the ‘vados zone’ — the space between the Earth’s surface and the groundwater below. The VMS made it possible to monitor hydrological and biogeochemical processes as well as elemental and nutrient fluxes in this zone that are critical for life and local ecosystems. More recently, and in collaboration with NCRIS-enabled AuScope, heat needles were installed to measure conductive heat flow at the earth’s surface. Consequently, The Calperum SuperSite is also fully-functioning as a Critical Zone Observatory site and contributes to the TERN-affiliated Australian Critical Zone network of similar observatories across the continent.

The influx of Critical Zone data is helping researchers characterise the changes occurring in the Mallee woodland. It’s revealing more and more about the landscape’s capacity for resilience, as well as the limitations of that resilience.

“It’s slowly recovering,” says Wayne, “but that’s going to become increasingly harder.”

“Our data indicate that the drying is now becoming just a little more persistent,” he says, explaining that the amount of evaporation is now consistently exceeding the amount of rainfall and this, in turn, will affect the Mallee system.

“The vegetation is incredibly well adapted to drought, but not persistent long-term drought,” he says. “It’s very unlikely that it can keep adapting. That’s become clearer since we’ve had the bore in there.”

Future work

It’s only a matter of time before a tipping point is reached, says Wayne. The impact on the rest of the Murray Darling Basin could be far reaching, but the timing and precise nature of such a tipping point are not clear, which is why ensuring the continuation of long-term data collection at Calperum is at the forefront of his mind.

Wayne estimates he’s made more than 130 trips out to Calperum over the years, but he knows there are only so many more times he can climb the tower and take in the remarkable view. He’s now looking to hand over the reins – or in this case the safety harness – to the next generation.

The story of the Mallee in the Murray Darling Basin will continue to reveal itself little by little. Things play out slowly in a place like this, and that’s precisely why we need to keep listening, says Wayne. Every bit of good quality, detailed data forms part of that story.

“The longer term that you collect the data, the more valuable it becomes simply because of that.”

Feature image credit: Wayne Meyer