Monitoring 1,000 plots across Australia’s vast landscapes required ingenuity in adapting and designing equipment that didn’t exist. Discover how TERN’s innovations to the Basal Wedge and Densitometer Pole helped make continental-scale ecosystem surveillance possible.

Australia’s vast and varied landscapes, from tropical rainforests to arid rangelands, have long presented a challenge: how do you consistently survey ecological change across an entire continent? TERN Australia tackled this challenge head-on by developing a world-first approach that has revolutionised how we understand ecosystem change at a continental scale.

At the heart of this innovation is a network of approximately 1,000 strategically placed one-hectare baseline plots spread across Australia’s diverse environments. These plots serve as permanent monitoring stations, providing crucial data about what is changing in our ecosystems, by how much, and in which direction over time. This groundbreaking methodology represents the first nationally consistent, long-term ecological plot survey program of its kind anywhere in the world.

Originally established in 2010 under TERN’s former “AusPlots Facility” and later integrated into TERN’s Ecosystem Surveillance capability alongside the Australian Transect Network, this approach became known as the TERN AusPlots method. Today, it continues to evolve through EMSA (Ecosystem Monitoring System Australia), extending users of TERN’s innovative approach to ecosystem survey monitoring.

Innovation born from necessity

Developing a monitoring program of this scale and consistency meant confronting a significant problem: there was specialised equipment for some of Australia’s diverse landscapes but nothing to address TERN’s need to collect standardised data across all landscapes. The multidisciplinary TERN team had to reimagine existing tools and techniques entirely.

The TERN Basal Wedge: seeing the wood for the trees (and shrubs)

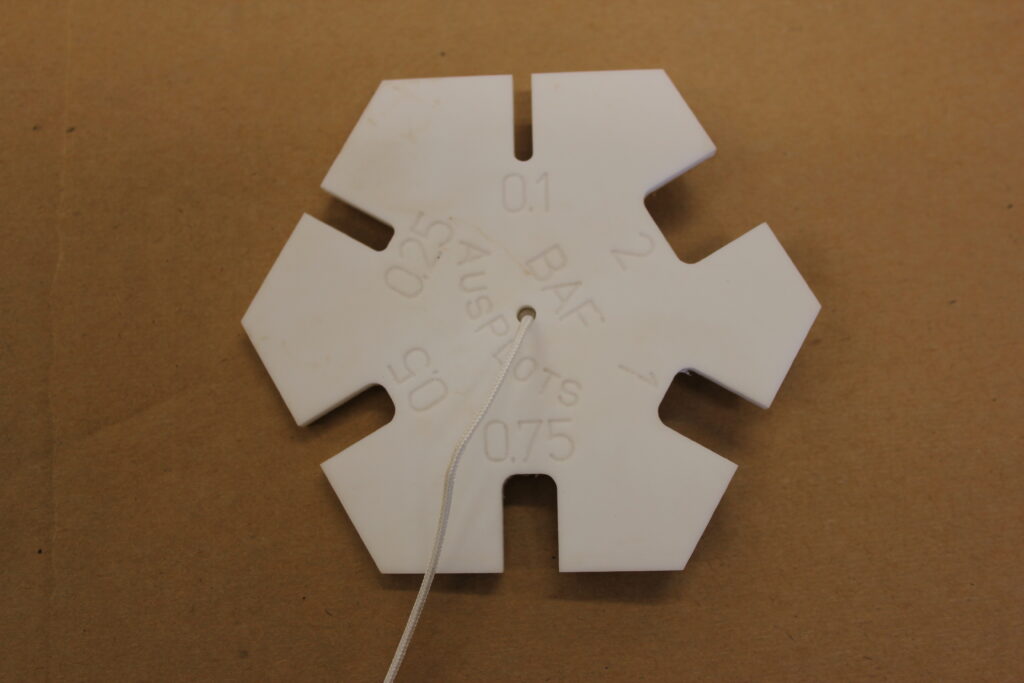

A standout example of TERN’s ingenuity is the TERN Basal Wedge, which has been adapted from a forestry tool to meet the unique demands of Australian ecosystem monitoring. This instrument enables field teams to collect critical data about vegetation structure, which is information essential for understanding ecosystem health, biodiversity, carbon storage, and how our landscapes are responding to climate change and land management.

Understanding how much woody vegetation exists in a landscape tells us about habitat structure, carbon storage potential and ecosystem function. This is where the basal wedge comes in. It is an optical tool that uses an elegant principle to estimate basal area (the cross-sectional area of tree trunks and stems, a key indicator of wood volume and biomass) without measuring every individual plant.

The concept originated with Austrian forester Dr Walter Bitterlich in the late 1930s and 1940s. By the early 1950s, researchers like Cromer in Australia and Grosenbaugh in the United States had recognised its value, and it became a standard forestry tool. The wedge works through angle count sampling: when you look through it and rotate 360 degrees, trees that appear wider than the wedge’s predetermined angle are counted, while narrower ones are not. While measuring every tree in a plot provides accuracy, it is generally not practical to do so, which makes approximation using a the basal wedge such a useful tool.

Top left: closeup of the Basal Wedge that forms part of the TERN AusPlots method; TERN ecologist lining up the Basal Wedge in the field; Lower image: Basal Wedge in use at Calperum (images courtesy of Donna Lewis & Ben Sparrow)

Traditional basal wedges, however, were designed for forests, not the open woodlands and sparsely vegetated rangelands that dominate much of Australia. Standard wedges typically offered only four or fewer basal factor sizes, which is insufficient for accurately capturing the range of woody vegetation densities across Australian landscapes.

TERN’s solution was the purpose-built TERN Basal Wedge, featuring six basal factors rather than the conventional four. This modification dramatically improved measurement accuracy in Australia’s characteristically open landscapes, where vegetation can be widely scattered. The TERN Basal Wedge has been a major asset to TERN as it systematically undertakes time-series vegetation community mapping across the continent’s diverse ecosystems.

Precision at every point

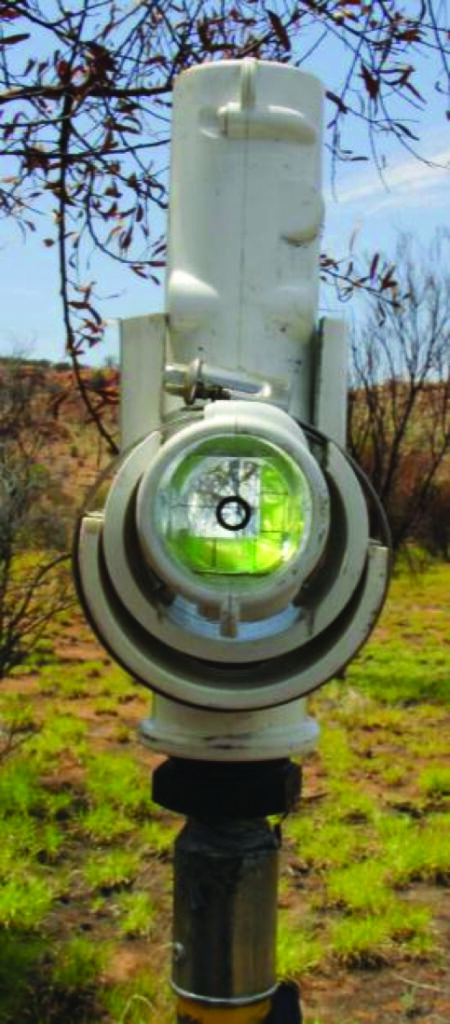

While the basal wedge addresses woody vegetation, understanding the complete picture of ecosystem structure requires measuring vegetation height and cover at multiple layers – from ground cover through to canopy. This information reveals habitat complexity; it tells us which plant species occupy which vertical spaces; and it helps track changes in vegetation composition over time.

Using tapes and a laser to ensure consistency over space and time, the TERN AusPlots method employs a rigorous point-intercept approach to estimate cover. Within each one-hectare plot, observers collect measurements at 1010 points, recording what vegetation (if any) intersects an imaginary vertical line at one-metre intervals, creating a detailed three-dimensional picture of vegetation structure. These data are invaluable for understanding biodiversity patterns, ecosystem processes, and vegetation responses to environmental change.

Clockwise from top left: TERN ecologist using a densitometer; closeup view of a densitometer viewer with cross-hair grid (images courtesy of Donna Lewis & Ben Sparrow)

Supporting the point-intercept methodology is a basic densitometer, a hand-held pole available commercially but modified for TERN’s systematic surveying by enclosing the densitometer optics in a PVC tee socket and attaching it to an extension pole ranging from 1.1 to 2 metres in height and marked at 10-centimetre intervals. This allows observers to record the precise height at which each plant species intercepts the vertical line of sight. To eliminate observer bias when assessing ground cover, TERN uses a laser pointer that projects a small, defined point on the ground surface, ensuring consistent and objective measurements. TERN has developed comprehensive guidelines for constructing and using this instrument, which are now shared with collaborators and researchers adopting TERN’s point-intercept methodology for their own survey monitoring programs.

A panoramic picture

Pre-dating ideas about AI by more than a decade, TERN’s inclusion of photopoints – better described a photo-panoramas – in its program is another innovation to standard environmental monitoring programs. The photo-panorama method enables use of the images as traditional photo-points (static photos) and seamless site panoramas (360o panoramas from three locations within the plot). With the application of algorithms, the panoramas can be processed to generate a 3D reconstruction of the plot, which provides measurements of basal area and biomass.

Photo-panoramas:

- provide a much more complete view of an ecosystem than traditional static photos.

- can be processed to generate 3D reconstructions of ecosystems, providing measurements of basal area and biomass.

- are easy to produce, requiring only three photos from different locations within the plot.

- provide a cost-effective way to collect data on ecosystems.

Eco-specimens for future analysis

TERN uniquely collects representative plant specimens, including associated leaf tissue, for every species at every plot, along with soil samples. This means all the essential data, vegetation and soil samples, which have been collected at the same time by the same team, are openly available to researchers in Australia and beyond. This initiative makes TERN’s data more future proof because the original ecosystem artifacts can be revisited for additional insights and verification, something that is essential when the taxonomic classification changes over time.

Impact beyond innovation

These innovations in equipment design and methods might seem like small technical details, but they represent something far more significant: they are the enablers of continental-scale ecological understanding. Without tools and protocols specifically designed for Australia’s unique ecosystems, TERN’s ambitious vision of consistent, long-term monitoring across the entire continent would not be realisable.

Today, data and samples from TERN’s network of plots, collected using carefully designed instruments and methods, flow into Australia’s environmental decision-making, support biodiversity conservation planning, inform land management strategies, and contribute to our understanding of how climate change is reshaping Australian ecosystems. TERN has many examples of what can be achieved when scientific ambition meets practical innovation: tools and processes born from the need to measure a continent, now helping to protect it.