Celebrating a mentor’s groundbreaking Nature review while rediscovering the magic of a familiar field site, this time from beneath the surface.

By Madeline Goddard

We are on a small, no-nonsense research vessel, rocking gently as we gaze back at the mangrove-lined shore. It’s mid-December 2025 and following a sunrise tour of Brisbane’s eastern suburbs and bleary-eyed ferry-ride to Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island, Queensland), we are preparing to dive in. Glancing overboard, we are welcomed by a large shovel-nose shark slicing through the seagrass meadows.

Part balancing act, part contortionist bending, sheer will power has me in a wetsuit. Snorkel ready.

TERNs OzSET team and members of the University of Queensland’s ‘Lovelock lab’ are on a unique fieldtrip: snorkelling through the mangroves to experience the abundance and diversity of coastal marine life at high tide. We are here to witness what is increasingly being known to the scientific community: that mangrove biodiversity is critical and underpins many ecosystem services, from fisheries to coastal protection.

The mangroves that fringe the northwestern side of the island are protected from large surf swells, allowing for the formation of a textbook profile: seaward seagrass meadows giving way to fringing mangroves and then a landward transition zone of saltmarsh, until finally arriving at a supratidal coastal paperbark forest. The tide is about to peak and we are going to snorkel along that profile as far as our giant flippers will take us.

Images courtesy of Madeline Goddard

This field site is well known to many of us at low tide, having been established as one of Professor Cath Lovelock’s field sites in 2007 and visited by waves of Lovelock lab researchers ever since. Cath is a marine biologist at the University of Queensland and she has been trekking through these muddy mangroves, lugging heavy gear to measure fine scale changes in elevation relative to sea-level rise for nearly two decades. When the tide drops, mangroves become a terrestrial, though somewhat damp landscape. Trees are the dominant vegetation, as mangroves distinctively lack an understory that would otherwise be a niche occupied by grasses, shrubs and other understory plants in a terrestrial forest. Despite the absence of an understory, mangroves are far from devoid of life. Crabs, snails, mudskippers, birds and – sometimes annoyingly – insects fill the fecund mangrove forest. The mangroves’ pneumatophores (aerial roots) are covered with epiphytic macro-algae, which provide myriad biogeochemical functions. This algal layer also protects the roots from desiccation and heat stress during low tide – a reminder of how much time mangroves spend as an aquatic system.

Gliding through with a snorkel at high tide, the mangrove canopy casts sepia tones of dappled light through the complex root system and we are totally immersed in a marine environment. We can see our field equipment, inundated and almost uninteresting in contrast to the life around us. Hundreds of tiny juvenile fish glimmer and dart through the roots, larger adult fish are also taking advantage of the complex root structures and newly available food. A small squid bobs by, and as I approach the landward saltmarsh margin, I jump back (as much as one can while snorkelling) as two large stingrays glide past. The abundance and diversity of life we are witnessing is exactly what recent research has shown is important for healthy mangroves and the vital ecosystem services they offer.

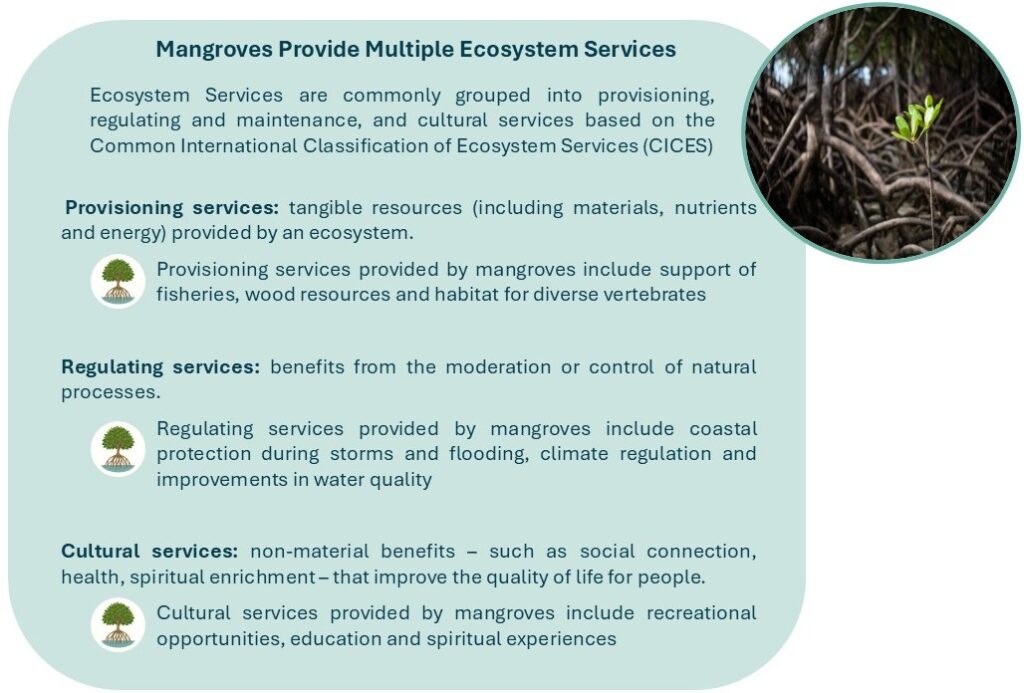

Cath, our snorkel guide today, is the lead author on a recent global review in Nature Reviews Biodiversity of mangrove biodiversity and ecosystem services. The review highlights that the biodiversity of mangroves underpins the ecosystem services we rely on. A mangrove is more than its trees. It is a community of plants, animals, fungi and microbes that work together to provide a large number of ecosystem services.

Immersed in this flooded forest, we witness these interactions. Complex root structures slow the tidal waters, allowing sediments to settle, burying carbon and building vertical elevation. They slow us down as well as we carefully navigate the buttress roots of the Rhizophora (red) mangrove tree. There are rays hunting for crustaceans that live in the soils and fish taking advantage of the food available only at high tide, all contributing to the energy influx and export in tidal waters.

The global review advocates that if mangroves are managed for single outcomes, such as equating tree-planting alone with ecosystem restoration, we miss more than the delight of a complex ecosystem. Cath and her colleagues argue that the multiple ecosystem services mangroves provide arise from the many processes and functions within these ecosystems. The research indicates that, without biodiversity, the benefits derived from mangroves are weakened and the ecosystem becomes less resilient over time.

The mangroves of Minjerribah have been an important food source and remain culturally significant to the Quandamooka people of the island after thousands of years. While western science has been good at quantifying and valuing the provisioning and regulating ecosystem services and regulation ecosystem services of mangroves, the cultural ecosystem services remain underacknowledged and undervalued. Despite the importance to local communities, it is often difficult to value cultural services, as determining the intrinsic value of the system remains an equation without numbers.

The Lovelock lab is a diverse and driven bunch of PhD candidates and early career researchers, led by ARC Laureate Cath Lovelock. Cath’s coastal ecology work spans decades and in recent years has led to practical tools for blue carbon restoration, spanning policy and science in the creation of the Tidal restoration for blue carbon method for the Australian Carbon Credit Unit Scheme (the carbon market), and developing an ACCU scheme method for wetland repair through feral ungulate management. She has contributed to advancements in contemporary coastal wetland science and recently published on empathy when integrating western and Indigenous science, asking scientists to cultivate their empathy in order to achieve better social and environmental outcomes as part of our practice. The biodiversity of mangroves review reflects the breadth and values of her body of work and emphasises a key theme: systems with diversity offer greater outcomes. Greater than the sum of her academic contributions, Cath’s mentorship and leadership amongst her students will lead to many other significant contributions to coastal wetland science and policy into the future.

As pressure on our coastlines increases, mangroves remain a beacon of hope. Their ability to adjust to sea-level rise, protect coastlines and capture and store atmospheric carbon means they are an active component in climate change mitigation. Being in our field sites without the demands of field work gives space for ideas to surface, for our community to connect, and for us to reconnect with the deeper values that guide our work. As we clamber back onto the boat, sharing what we saw as the boat pulls away, it is clear that value comes from the whole forest, not just the trees.