Data from one of the world’s longest running arid-zone ecological monitoring projects, now openly available via TERN’s infrastructure, is helping resource, land and environmental managers answer important questions about the ecology of arid zone vegetation and the changes grazing and climate change have on arid ecosystems.

Since the mid-1920s scientists and students from The University of Adelaide have been studying the regeneration of natural vegetation at Koonamore Vegetation Reserve, part of a sheep-grazing lease 400km north-east of Adelaide, making it one of the world’s longest-running ecological monitoring projects of its type.

Koonamore Vegetation Reserve was established by Professor TGB Osborn to study the ecology and regeneration of the natural arid zone vegetation after the influences of sheep and rabbit grazing were removed. It is now formally named in his honour ‘The TGB Osborn Vegetation Reserve, Koonamore’.

90-years of mostly continuous monitoring and data collection at the site have captured a complete history of the site’s vegetation, represented by an exceptionally diverse set of population-related observations totalling almost 250,000 records. The Koonamore dataset provides a smorgasbord of population-related data on some of Australia’s iconic arid plant species.

These exceptional data are now integrated with other data from arid Australia and available for download via the Australian Ecological Knowledge and Observation System (ӔKOS), providing an invaluable source of information for arid ecologists.

|

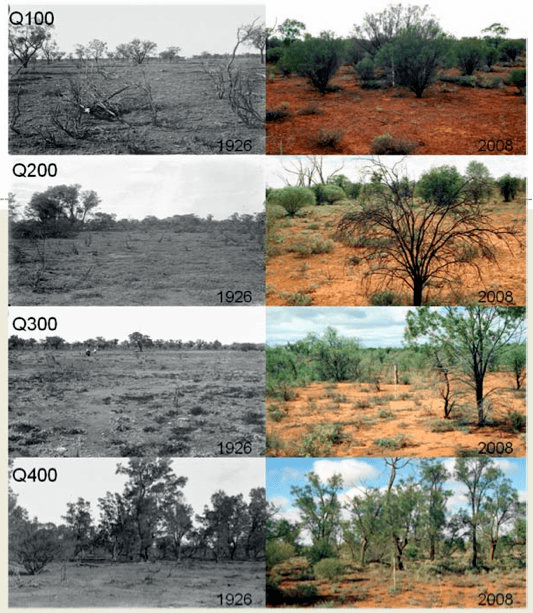

| There are more than 8,000 photographs now available via ӔKOS, such as these before and after shots taken in 1926 and 2008, that enable sophisticated species analyses and show how vegetation has changed in the absence of grazing. |

Research studies using Koonamore data are ‘Helping answer important questions about the ecology of arid zone vegetation and the impacts grazing and climate change have on arid ecosystem functions,’ says Associate Professor José M. Facelli of the University of Adelaide.

Only answerable via long-term studies, such information is vital to resource and land managers across Australia’s arid rangelands, which make up 81% of the continent and support significant parts of the nation’s economy, including mining (in excess of $12 billion), tourism (greater than $2 billion) and pastoralism and agriculture combined ($2.4 billion in 2001), and in similar arid environments around the world.

For example, Koonamore was instrumental in facilitating research during the UNESCO Arid Zone Research Program and in the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program on Global Warming. These seminal international studies are, at least in part, responsible for major advances in our understanding of arid ecology – especially in the area of community-physiological processes and arid ecosystem modelling under a changing climate – and can be linked to the generation of improved arid zone and rangeland management actions.

Moreover, Koonamore has facilitated a huge number of collaborative scientific studies on such topics as arid zone grazing, native vegetation changes, soil salinity, drought tolerance, and carbon fluxes.

‘Despite these studies there is still a great deal about these fragile ecosystems that we don’t understand,’ says José.

Open access to these data, via TERN Eco-informatics’ ӔKOS, is expected to facilitate the science to fill this information gap. Science not only on the environment in northeast South Australia, but also on arid ecosystems throughout Australia and overseas created as researchers ‘scale-up’ the data and combine and compare them to other ecosystem studies.

The Koonamore dataset contains a history of the vegetation over 50 years without sheep grazing followed by more than 30 years without significant grazing by either sheep or rabbits.

The data are population-related observations that have been undertaken at the Koonamore Vegetation Reserve as early as 1923 when the first photopoints were recorded at 67 locations through the reserve. There are more than 8,000 photographs now available via ӔKOS enabling sophisticated species analyses and showing how vegetation has changed in the absence of grazing.

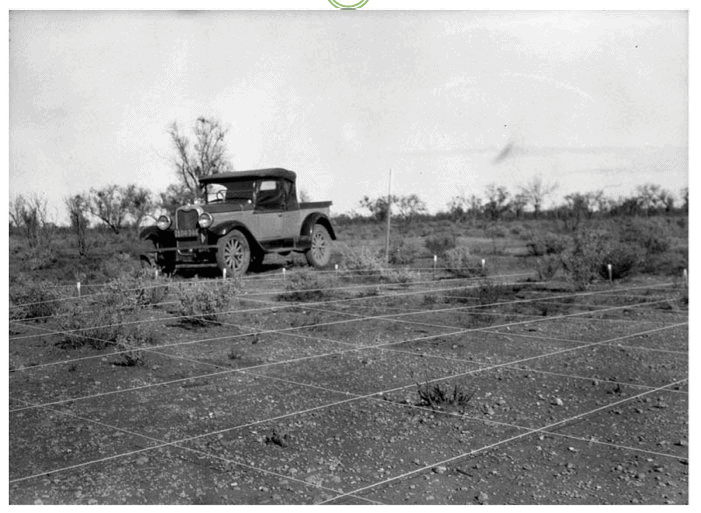

Additionally, data have been gathered from several permanent quadrats within the Reserve, the largest being 100x100m squares. Species identity, position, height and canopy width are recorded for the larger trees and shrubs, including Myoporum, Acacia, Casuarina, Atriplex and Maireana species. These data can be freely downloaded. Data also exist on the impacts of rabbit grazing prior to their exclusion and kangaroo grazing over the history of the reserve (kangaroos and emus have never been excluded).

Click here to watch a video on how to access Koonamore survey and integrated site data in ӔKOS

|  | |

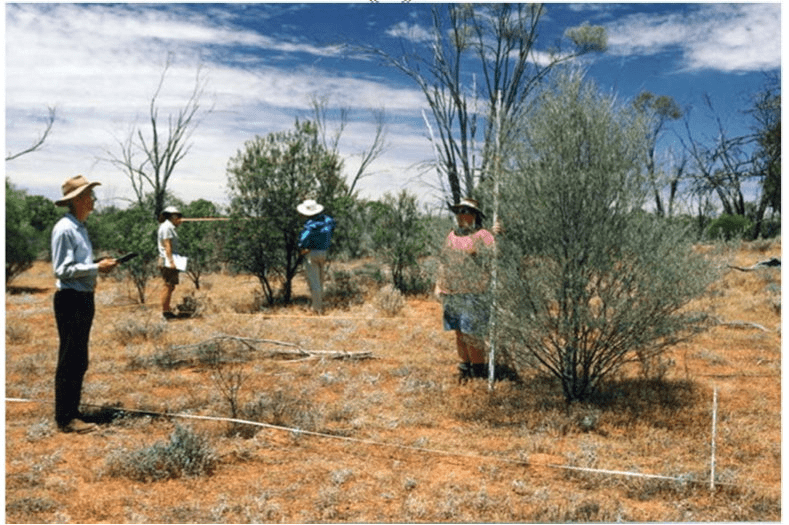

| Setting up monitoring quadrats at Koonamore in the 1920s (left) and collecting observations from them in 2008 (right) | ||

Throughout the decades the Koonamore project has been supported by students, researchers and volunteers who have conducted valuable monitoring and maintenance work including retaking photopoint photos, remapping the permanent quadrats, re-reading permanent transects and maintaining the sheep and rabbit exclusion fences.

‘As a volunteer I found Koonamore Vegetation Reserve to be a peaceful slice of landscape which is incredibly unique,’ says Alexandra Bowman, who recently received her PhD from the University of Adelaide..

‘Having conducted some of my PhD with Koonamore as a field site, I have further learnt how truly unique the reserve is; the long term data collected and the stark difference between inside and outside the reserve provide a wealth of opportunity for studies of arid land ecosystems.’

Another volunteer, Dean Graetz, echoes Alexandra’s sentiments, saying ‘Koonamore, and the research conducted there, remained of interest and inspirational to me for the 30 plus years I worked as a CSIRO research scientist.’

However, Dr Russ Sinclair, who oversees the work at the reserve alongside José, says that ‘Koonamore cannot continue on the generous support of passionate volunteers alone. It needs regular and ongoing funding to ensure that this project can continue its great work.’

Financial support has come from a number of areas including the University of Adelaide’s former Botany Department, bequest funds to the university for research in arid areas, and grants from Nature Foundation SA and the Native Vegetation Council.

‘Koonamore has survived because it has been supported by a stable institution and a succession of individuals dedicated to maintaining the project,’ says Russ. ‘Such success also depends on a secure and long-term source of funding.’

To help ensure the continuation of the Koonamore project, The University of Adelaide invites you to join the group of individuals who are making a difference by supporting this fantastic environmental project. A donation to this project will continue a tradition of support for Koonamore and ensure future students and scientists have long-term access to this valuable research facility and the remarkable data resources and science it generates.

- For further enquiries on Koonamore or to make a donation please contact The University of Adelaide’s School of Biological Sciences.

- For more information on the ӔKOS data portal please contact TERN’s Eco-informatics facility.

- Click here to watch a video on how to access Koonamore survey and integrated site data in ӔKOS

Published in TERN Landscape Observation Newsletter September 2015