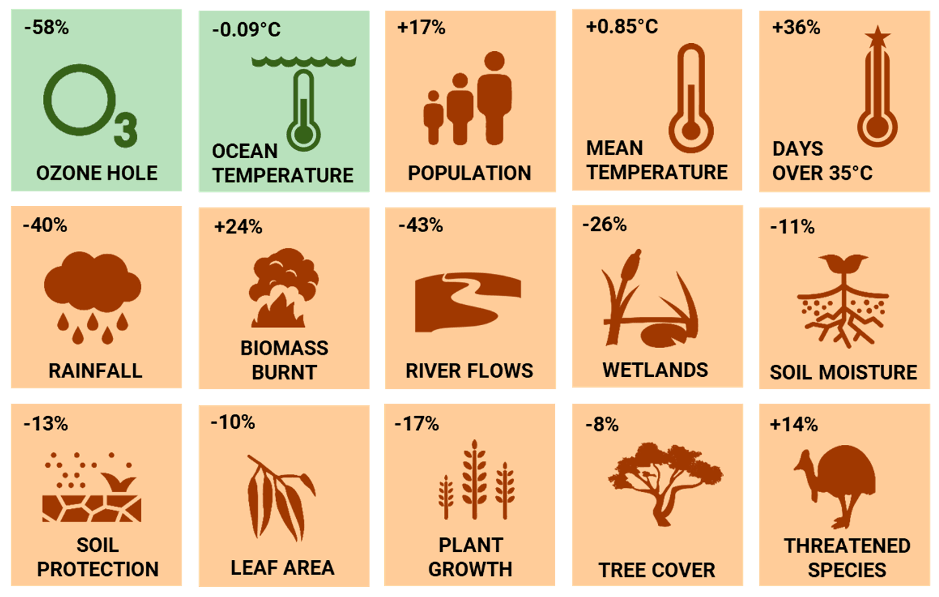

Temperatures up, rainfall down, and the destruction of vegetation and ecosystems by drought, fire and land clearing continued. That is the main conclusion from Australia’s Environment in 2019, the latest in an annual series of environmental condition reports, released on Monday 30 March 2020. The ecosystem studies report, and its website, provide a summary of 15 key environmental indicators and how they have changed over time.

Unfortunately, at a time when we crave positive news, the report makes for grim reading: a story of extreme drought, heat and damage to our natural capital.

Nationally, Australia’s environmental condition score fell by 2.3 points in 2019, to a very low 0.8 out of ten—the lowest since at least 2000, the start of the period for which detailed data exist.

“Globally, greenhouse gas concentration continued to increase rapidly. With it, the temperature of the atmosphere and oceans soared, and sea ice retreated further.

In rare good news, the Ozone hole was much smaller than the previous year, helped by unusual air circulation over Antarctica. Around Australia, ocean temperatures were less hot than the year before. Although the Tasman Sea was once again very hot, marine heatwaves did not occur to the same extent as in previous years.

Unfortunately, last year was neither an outlier nor the ‘new normal’. Instead, it was just another step down on the continuing descent into an ever more dismal future – unless we finally take serious action.”

Albert van Dijk, ANU

2019 was a year of record drought, heat and fire

Collating vast numbers measurements on the state of our environment

The report and website are created by the Australian National University’s Water and Landscape Dynamics group (ANU WALD) by analysing vast amounts of measurements from satellites and on-ground stations using algorithms and prediction models on a supercomputer, including many delivered by NCRIS-enabled projects, including TERN.

The algorithms and models use the open data to summarise 15 key environmental indicators. From these 15 indicators, seven were used to calculate an Environmental Condition Score (ECS) to allow analysis as to how they have changed over time for any region in Australia.

New this year, report cards can be downloaded for any administrative or geographic region of Australia, including local government areas, electorates and bioregions, for example.

“The ECS score uses indicators related to hot weather, river flows, wetlands, soil health, vegetation condition, growth conditions and tree cover.

We know that they’re incomplete and different indicators could have been chosen, but the majority of them respond strongly to water availability and move up and down together, which gives the score more robustness.

Albert van Dijk, ANU

We can only deliver our annual report because we can openly-access trusted, national data from a range of nationally funded research infrastructures, and then use the National Computing Infrastructure’s supercomputer to integrate and analyse them.”

Prof van Dijk also says that of particular importance to the analysis are time-series data. These datasets allow patterns of change in Australia’s ecosystems to be assessed, which is critical to understanding and managing our environment.

The core of the annual report is the OzWALD system, a model-data assimilation system that integrates a wide range of satellite and station observations. The team’s next challenge is to develop OzWALD as an environmental prediction system, so that the impacts of weather and fire events on natural resources and ecosystems can be forecasted weeks to months ahead.

We’re not doomed yet

Importantly, Prof van Dijk and his co-authors say that all is not lost and that we still have time to act to buck the trend. They give practical solutions to help our natural ecosystems recover from the drought and fires, including managing invasive species in fire affected areas, donating money or time to organisations committed to helping ecosystems recover and participating in citizen science programs.

Beyond these short-term solutions, we finally need to get serious about greenhouse emissions. We can recycle and reuse rather than buying new, choose for low-emission and renewable energy technology in our houses, and reduce our waste.

We can let governments and politicians hear our voice. We can try to convince our friends and family that things need to change.”

Albert van Dijk, ANU

The researchers point to the current COVID-19 pandemic and how it has led to the world taking quick, dramatic action in the face of a significant threat. Similarly strong action to address environmental decline is possible and will cost far less than the long-term costs of not doing so.