TERN environmental data and infrastructure have been used to map South Australia’s biodiversity hotspots, identify their climate change sensitivity, and ultimately inform priorities and strategies for conservation management.

|

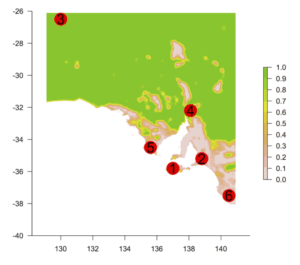

| TERN’s research and data infrastructure has been used to identify six major plant biodiversity hotspots across South Australia. This image above shows the hotspot locations over a map of the proportion of uncleared native vegetation remaining locally. Areas with low scores are highly fragmented (with the exception of the large salt lakes that have no vegetation). Of the six biodiversity hotspots, the southern Flinders Ranges (below) was found to be the most sensitive to climate change. Images courtesy of Greg Guerin. |

|

TERN’s research and data infrastructure has been used to identify six major plant biodiversity hotspots across South Australia. Alarmingly, researchers say that these regions are all under threat from a cocktail of habitat fragmentation, invasive species, altered fire regimes and climate change.

The six hotspot regions identified are: Western Kangaroo Island, Southern Mount Lofty Ranges, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands, Southern Flinders Ranges, Southern Eyre Peninsula and the Lower South East.

To identify these regions of exceptionally high plant diversity (or biodiversity hotspots), University of Adelaide researcher Dr Greg Guerin and colleagues compiled over 700,000 plant species records—and mapped them against attributes of species diversity and threatening processes. The records were obtained from the State’s Biological Survey program and TERN AusPlots field surveys, made openly accessible via TERN’s ÆKOS data portal*.

“Previously we just relied on expert opinion to identify where important areas of biodiversity were,” says Greg. “But now, thanks to data infrastructure like TERN’s, this is the first time we’ve been able to compile this large data resource and to systematically map out plant biodiversity using numerical methods.”

“Having access to the State data together with TERN-collected data from one portal [ÆKOS] really helped me to be efficient and publish my work earlier than planned.”

“I also archived the study’s derived dataset with a DOI in ÆKOS using TERN’s SHaRED data submission tool to help with research transparency and facilitate re-use and further research.”

Hotspots under threat

By merging the biodiversity maps with information on habitat fragmentation, climate sensitivity, fire frequency and weed prevalence the team was able to determine how threatened each hotspot is to key environmental change agents.

Of the six biodiversity hotspots, the southern Flinders Ranges was found to be the most sensitive to climate change. However, researchers warn that all six hotspots have serious conservation issues from habitat fragmentation, weed invasion and/or altered fire regimes.

“Further work into how these biodiverse areas are likely to change in the future is vital,” adds Greg.

Climate change is expected to have a major impact on biodiversity, but exactly how species diversity and composition will respond is difficult to predict. Professor Alan Andersen, of CSIRO and Charles Darwin University, says that one approach to understanding how species might fare under a changed climate is to examine what is happening where that climate already exists.

“This makes TERN’s network of monitoring transects that traverse Australia’s major bioclimatic gradients powerful observatories for understanding potential impacts of climate change,” says Alan.

“Researchers are describing patterns of species diversity and distribution along these transects, and many include nationally important biodiversity hotspots. For example, along the TREND [Transect for Environmental Monitoring and Decision Making], which passes through the southern Flinders Ranges hotspot, researchers are using the TERN-supported infrastructure to understand the rapid species turnover that occurs in certain climatic and rainfall zones.”

Conservation management tools

Biodiversity hotspot maps, together with information on future threats and habitat condition, provide an invaluable tool for informing conservation management. Greg’s team is hoping that their research will be the basis for conservation work in these most important areas.

“We expect local and state management authorities will be able to use our research into biodiversity hotspots and their threats to set priorities and strategies for the active management of native vegetation,” says Greg.

This biodiversity research and its use of TERN’s data and monitoring infrastructure is yet another example of how TERN is helping Australia’s research community work more collaboratively, efficiently and effectively.

The work is also an excellent showcase of what can be achieved using TERN’s integrated ecosystem observatory system, in this case, integrating across field infrastructure and curated data from TERN Eco-Informatics, TERN AusPlots and TERN’s Australian Transect Network.

- All the data used in this research are available for access and re-use through TERN’s ÆKOS data portal.

- *The study also used records from herbarium specimens held at the State Herbarium of South Australia, a database of some 400,000 individual occurrences of 4,500 different plant species, available through Australia’s Virtual Herbarium. State Herbarium Records are not currently available in TERN’s ÆKOS portal.

Published in TERN newsletter September 2016