Numerical models are key tools for decision makers in areas as disparate as weather forecasting, water security, ecosystem impacts, and climate mitigation and adaptation. They test the likely implications of particular management strategies or of greenhouse gas emission trajectories associated with particular economic development pathways. They are integrated into the decision-making frameworks of individual farm businesses through to local, state and federal governments.

They also allow researchers to test their conceptual understanding of how natural systems function from molecular to global spatial scales and on time scales from seconds to thousands of years. They provide the ability to investigate carbon budgets (the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide in a given system), water budgets (the balance of water coming into and leaving a given system), ecosystem dynamics and the sensitivity of natural systems to particular types of perturbations.

Models need to be regularly compared with and critiqued using actual observations – real-world data. Understanding the aspects of a natural system that a model captures well and those that it does not is one step in quantifying uncertainty in model predictions. Observations are not only used to benchmark the performance of models, but also to refine the assumptions on which model predictions may be based. Observational data are particularly powerful when they can do both of these things and simultaneously constrain several aspects of a modelling system. For example, the simultaneous integration of site-based carbon dioxide and water fluxes, soil litter pools and catchment-based stream flow reduces the uncertainty in estimates from models of Australia’s continental carbon budget.

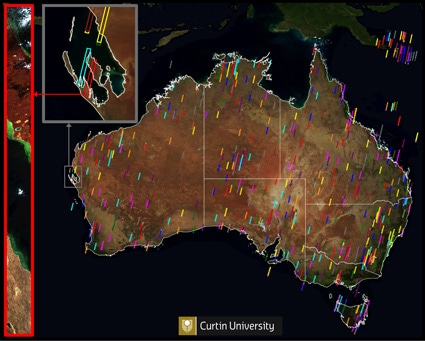

The e-MAST facility is building on the wealth of observational data streams from other TERN facilities to maximise their impact in modelling systems. These systems include the land-surface component of climate models, hydrological models and ecosystem models. Most of the models were developed before the types of data streams that TERN provides were in existence. More recently, issues such as data formatting and standardisation have meant that the uptake of ecological data in modelling communities has remained limited. The e-MAST facility is resolving some of these issues by processing and formatting ecological data specifically for model-based experiments, structuring experiments that can use this data to improve models, and supplementing existing datasets where missing variables would prevent their uptake. Through data-assimilation techniques (the process by which observations are incorporated into a model), e-MAST is also using hybrid data-model approaches to try to infer otherwise unobservable ecosystem properties at continental scales.

The model-formatted data streams, modelling experiment structures and hybrid data products are being published through a web application, the Protocol for the Analysis of Land Surface models (PALS). Even in its initial phase of implementation, PALS has attracted more than 125 users from the Australian and international land-surface modelling communities. The functionality of the system was illustrated at the ‘Smarter workflows for ecologists’ workshop at the Ecological Society of Australia annual conference early this month. It will be demonstrated again at the TERN symposium in February.

An example of an automated model analysis from the PALS web application, illustrating different uses of observed data for model benchmarking. The four plots show seasonal differences in the diurnal variations of the net ecosystem exchange of carbon dioxide from the Howard Springs flux tower. Observed values (black) are compared with those from a land-surface model driven by measured meteorology (blue), as well as those derived from three meteorologically based empirical predictions trained using data from other flux-tower sites.

Published in TERN e-Newsletter December 2012