Seven decades of long-term monitoring data from the Alps, now openly available via TERN infrastructure, are not only increasing our understanding of impacts such as fire, grazing and exotic species invasions, but also informing land-management decisions by government agencies and private enterprise and helping document a small but important part of the Alps’ natural heritage.

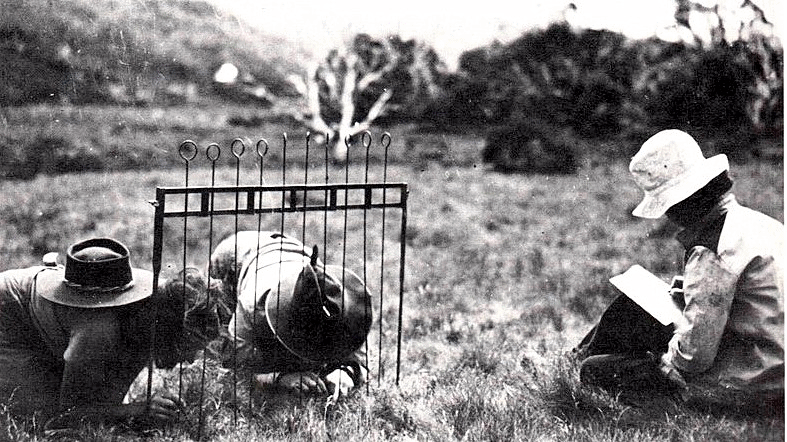

Scientific research in the Australian Alps has a long and rich tradition. Detailed ecological surveys commenced in the 1940s with the work of Maisie Carr and John Turner on Victoria’s Bogong High Plains, and Alec Costin and colleagues in the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales. Much of western knowledge about the Alps is based on discoveries made by these pioneers of Australian ecology.

In 1947 Maisie and John established the first long-term monitoring plots at Rocky Valley and Pretty Valley on the Bogong High Plains. These plots have been maintained to the present day and are now an integral component of the Victorian Alpine Plot Network—one of 12 long-term plot networks across Australia integrated by TERN’s Long Term Ecological Research Network (LTERN).

Building on Maisie and John’s work, the next generation of alpine ecologists expanded the number of sites in the 1970s and 80s to document ecological change in relation to disturbances such as grazing and ski resort development, and again following bushfires in the 90s and 2000s to quantify patterns of burning and to monitor post-fire regeneration.

With a continuous succession of scientists working on an expanding network of plots (today there are more than 50), the value of the Alpine Plot Network for documenting environmental change, and indeed intangible cultural heritage, is inestimable.

70-year alpine dataset now openly available

70-years of environmental data collection methods at the Victorian Alpine Plot Network have captured a long history of the sites’ vegetation and groundcover condition change, represented by an exceptionally diverse set of population-related observations totalling over 200,000 records.

These exceptional data provide an invaluable source of information for alpine ecologists and are now openly available for download from the LTERN Data Portal and discoverable alongside all TERN data via TERN’s Data Discovery Portal.

“This unprecedented dataset allows scientists to ask and answer questions about long-term alpine ecosystem dynamics and their vulnerability to changing patterns of climate, fire and land-use pressure in the coming century,” says Dr John Morgan of La Trobe University’s Research Centre for Applied Alpine Ecology who leads the Alpine Plot Network within LTERN.

“Open access to these data is a fantastic achievement, not just for all the work that’s gone into digitising trunkfuls of hard copy data! It’s exciting to think about all the new alpine ecosystem science that these data will facilitate at home and abroad as researchers scale-up the data and combine and compare them to other studies.”

Data the key to anticipating environmental change and achieving sustainable land use

These data and the findings of long-term studies using them are already having major influence on decision-making in the sustainable management of Australia’s alpine ecosystems.

Documentation of the dynamics of alpine vegetation, and the distribution, population structure and reproduction of important species, such as the endangered mountain pygmy possum, has had a major influence on the establishment of conservation reserves, such as Kosciuszko National Park in NSW, and Alpine National Park in Victoria. These data will continue to inform national park management in the coming decades.

Detailed data and robust science on threatened species and the fundamentals of ecosystem structure and function are used extensively to direct conservation, weed and fire management programs in ski resorts, for example at Falls Creek, Mt Buller and Mt Hotham. Over the past 5-years these relationships have been enhanced, thanks to the advent of LTERN.

Data from the long-term monitoring sites also provide clear answers to questions about the impacts of disturbance on alpine ecosystems. For example, cattle grazing, and its cessation, have both had profound effects on alpine ecosystems.

The data have also been an integral part of science investigating post-fire regeneration and ecosystem resilience and are invaluable for interpreting the changes seen in the warming experiments undertaken on the Bogong High Plains over the past decade as part of the International Tundra Experiment.

Long-term research for a sustainable future

Thanks to decades of persistent and fit-for-purpose ecological monitoring effort and infrastructure investment in the Australian Alps, we now possess detailed knowledge of the fundamentals of ecosystem structure and function. But the value doesn‘t stop here. Long-term research needs to continue in Australia to enable a sustainable future and to provide an adequate evidence base for management decisions.

The type of detailed monitoring undertaken in the Alps, allows us to anticipate environmental change and decide how best to manage the land for sustainable use. But according to Dr Dick Williams of Charles Darwin University who worked on the sites for more than 30 years, the understanding gained from this research has also highlighted its current limitations.

“70 years is a short time in the Alps, and there are still many things we don’t understand,” says Dick. “Long-term monitoring will always be vital for increasing our understanding, anticipating change and managing the alpine environment for sustainability.”

The value of long-term research is often under recognised in Australia as we focus on what new things we need to do to meet our emerging challenges. But sometimes being present in a landscape and taking repeat measures through time is the most innovative and important thing one can do to understand that landscape, how it is changing, and how it is likely to change in the future.

- Click here to explore and download seven decades of data from the Australian Alps.

- TERN would like to thank Dr Dick Williams for his contributions to this article, in particular, for his rich knowledge of the history of ecological research in the Alps.

- For more information on the Victorian Alpine Plot Network please contact Dr John Morgan of La Trobe University.

Published in TERN newsletter June 2017