Now is an exciting time in ecosystem observation, research and management. A number of visionary initiatives have been initiated over recent years in Australia and globally. A number of these initiatives have a commonality in their vision, namely to enable the collection, coordination, and delivery of ecosystem ‘health’ information and services to users, particularly decision-makers—to enable effective and timely conservation and sustainable use of ecosystems. And in so doing, generate the knowledge so urgently required to conserve and manage ecosystems and the services provided for societal benefits.

To name but a few of these visionary initiatives, here in Australia we have TERN, the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) (both NCRIS funded projects), the Ecosystem Science Council (ESC), the National Environmental Science Programme (NESP), the Academy’s Future Earth Australia Project; and globally we have the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Ecosystems, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), and the Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON), part of Global Earth Observation System of System of Systems (GEOSS).

As well as having a common vision, a number of these initiatives also have a common date for goal evaluation, 2025.

|

For a modest annual investment of $30 million in TERN, Australia could become a global leader in trans-disciplinary research and knowledge transfer, and in the design and use of computational technology for environmental science |

TERN sees Australia as a world leader in ecological science and the application of this science for healthy, productive and valued terrestrial ecosystems. As a relatively well-developed country that is home to globally unique flora and fauna assemblages and landscapes we have both responsibility and a unique opportunity to develop and implement scientific solutions to issues of sustainable resource use, biodiversity conservation and climate change responses (mitigation and adaptation).

To this end, by 2025 TERN envisages a world where its infrastructure will be used widely across the scientific and environmental policy-making community, playing a critical role in enabling Australia to track and understand ecosystem changes at a continental and priority broad biome level and that its infrastructure is integrated into global ecosystem science initiatives.

Similarly, by 2025, IMOS envisages Australia will have a continuously growing time series of essential ocean variables for marine and coastal environments. Internationally, IUCN seeks to have assessed all the ecosystems of the world by 2025 and GEO BON will be a robust, extensive and interoperable biodiversity observation network covering the major biomes of the globe.

Thanks to future-thinking, collaborative initiatives like TERN, Australia is now in a good position to capitalise on the gains of the past five years and achieve its 2025 vision of Australia becoming the global leader in ecosystem science. However, knowledge and policy gaps remain in important areas of ecosystem science. In our most recent report under the NCRIS program, Ecosystem data for the nation, we explored the consequences of three levels of funding. A maintenance level of $10 million a year would support most existing capabilities; and a continuation level of $20 a year would run the full suite of NCRIS-established TERN capabilities.

However, for a modest annual investment of $30 million, Australia could become a global leader in trans-disciplinary research and knowledge transfer, and in the design and use of computational technology for environmental science. Perhaps more importantly, TERN infrastructure could address urgent gaps in existing capabilities that would allow Australia to transfigure our understanding of ecosystem resources. This would provide the knowledge base for policy and management choices that optimise the safeguarding of soil and water resources and of native species, and lead to improved agricultural productivity, urban and rural communities that are able to flexibly accommodate environmental change, the mitigation of threats such as fire and pests on ecosystems, and the harmonious cohabitation of native species and economic activity.

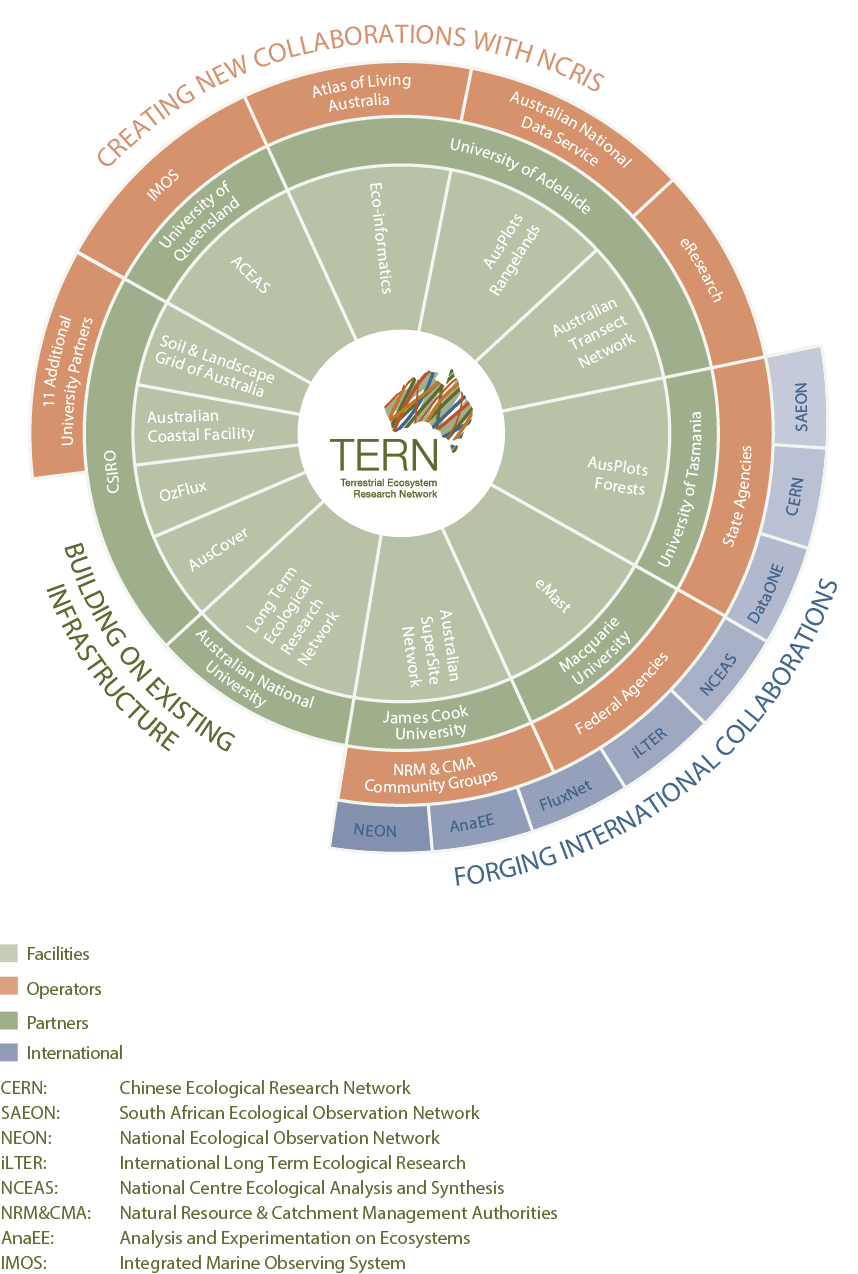

If Australia is to achieve this by the year 2025, there is a need for complementarity, collaborative and cohesive approaches in addition to appropriate resourcing. To this end, collaboration is at the heart of what we do here at TERN. Our collaborative model of research is enabling more effective use of the limited budget available for applied problems in Australian ecosystem science—successfully harnessing existing efforts across the country and enabling everyone to pull in the same direction.

In a recent example, TERN has enabled linkages through joint membership to the Ecosystem Science Council, and the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems (RLE) team thanks to our Long Term Ecological Research Network (LTERN) Facility. In the case of the RLE, this has enabled LTERN to help develop and test the Red List of Ecosystems protocols and criteria. A recent special issue of Austral Ecology showcases the application of LTERN expertise and data in providing detailed risk assessments for a diverse selection of Australia ecosystems—from the coast to the central deserts, the tropics to the temperate regions, and from the mountains to the sea. In applying the IUCN criteria to these ecosystems, researchers aimed to identify the defining features of their systems and the processes that threaten them, evaluate trends in key variables relevant to the persistence of the ecosystems, and assess the risk of ecosystem collapse in the 21st century.

LTERN Plot Leader, Professor David Keith, and his RLE team received the 2015 Eureka Prize for their development of the scientific underpinnings of the RLE assessment criteria. By contributing advanced scientific methods and data, LTERN has helped place Australia at the forefront of this important global innovation. It has also enabled joint participation in strategic planning to facilitate cohesion and complementarity, where feasible. For example, in November 2015, LTERN and the ESC, were able to attend the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems strategic planning meeting in Melbourne. It is hoped there will be future opportunities to collaborate and seek alignments.

|

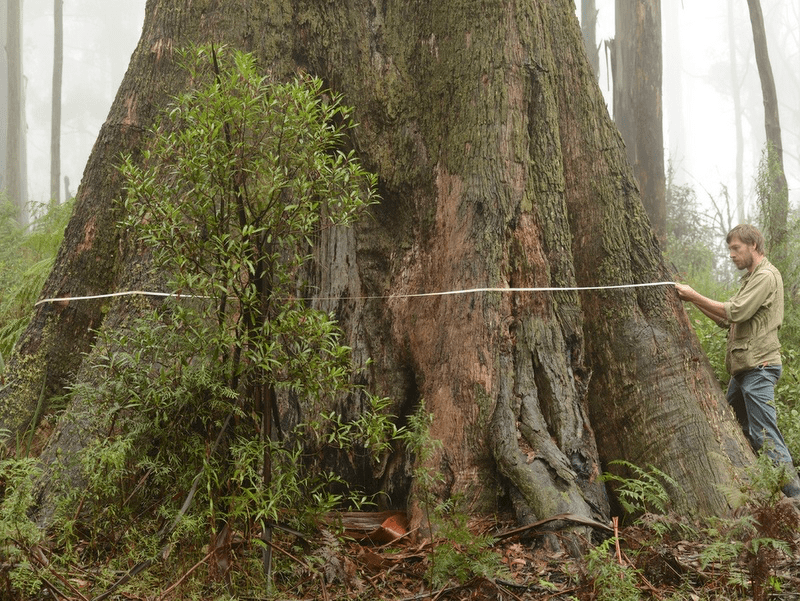

| TERN facilitated research has discovered that the Mountain Ash forests of Victoria’s highlands are at very high risk of collapse, leading to the up-listing of the Leadbeater’s possum to ‘critically endangered’ |

|

These collaborations are already paying scientific and conservation dividends. For example, LTERN researcher’s utilised decades of scientific monitoring from the Victorian Tall Eucalypt Forest Plot Network and discovered that the Mountain Ash forests of Victoria’s highlands are at very high risk of collapse within half a century, driven by the effects of clearfell logging and bushfires. In fact, all 39 scenarios modelled indicated a ≥ 92% chance of ecosystem collapse by 2067, which led researches to class the ecosystem as Critically Endangered in their paper, Ecosystem assessment of mountain ash forest in the Central Highlands of Victoria, south-eastern Australia

This research was influential in the recent up-listing of Victoria’s Leadbeater’s possum to ‘critically endangered’ by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee. It was communicated through The Conversation and The Ecologist, generating heated debate and was later also translated into high school curriculum support material.

This research is also being utilised as a case study in one of TERN’s newest projects: the CoESRA virtual experiment environment. CoESRA provides an interface for people to see the workflow and steps taken to produce a study’s findings so that the entire experiment is reusable and reproducible. There is a significant public interest in the management of mountain ash forests and it is important that the science underpinning assessments of threat status are open as well as the opportunity for informed debate about future management options to be facilitated.

Due to Commonwealth investment in TERN, for the first time in the history of Australian ecosystem science, infrastructure exists that enables ecosystem scientists to collaborate and share data efficiently and effectively across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally. Most of the ecosystem science problems we face are simply too big and too complex to deal with in any other way.

TERN’s collaborative infrastructure and networks are not only transforming the way Australian ecosystem science has traditionally been done; we are delivering better returns on investment in ecosystem science for this country. TERN’s infrastructure helps bring the solutions to the pressing environmental challenges faced by Australian communities and industries within our reach, for the first time. What has been achieved to date is only part of a longer journey; one that is engaged in fully will allow Australia to take a global leadership role in ecosystem management for multiple benefits.

Published in TERN newsletter December 2015