New insights from extreme years as flooding rains interrupt prolonged drought

In comparison with drylands elsewhere, the unpredictability of rainfall in central Australia is globally distinctive. The transformative rhythms of arid Australia reflect extremes of climatic conditions rather than seasons, and are characterised by irregular pulses of productivity that punctuate long periods of drought.

It is in this setting in the Simpson Desert in south-western Queensland that you will find the Desert Ecology Plot Network, part of TERN’s Long Term Ecological Research Network (LTERN).

A team of researchers led by Professor Chris Dickman and Associate Professor Glenda Wardle from The University of Sydney has, with TERN support, been working to understand the patterns and processes at work in this environment for over 20 years.

Although average annual rainfall for the area is recorded as 200 mm, averages are a poor indicator of what actually occurs in this environment. Typically there are prolonged periods of drought episodically interrupted by intense rainfall events, resulting in a boom–bust pattern.

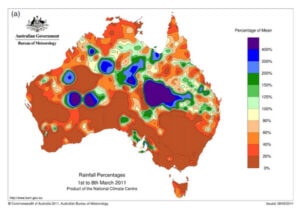

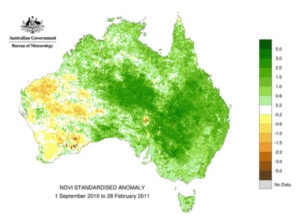

In 2010 and 2011 flooding rains broke long-standing rainfall records and triggered a greening of the typically dry red landscapes of central Australia.

The change gave scientists an unparalleled opportunity to test ideas about landscape productivity and function and the various responses of biota to such extreme events that reflect landscape connections and diversity.

|  | ||

|  | ||

|

Clockwise from top left: A downpour over Cravens Peak in central western Queensland in November 2011; ecologist Glenda Wardle of Sydney University collecting data in the Simpson Desert; ecologist Tony Popic bagging Crotolaria cunninghamii; and Ethabuka Spring in south-west Queensland. (Photos courtesy of Aaron Greenville and Glenda Wardle)

Often ecologists wanting to study such an extreme event would be scrambling to bring together sufficient resources to complete a reactionary one-off study. However, the nature of LTERN’s long-term environmental monitoring programs means that its desert ecologists were already on hand to document these unusual extreme climatic events. They also had years of data to compare their findings to.

All their hard work is now on show and has been featured in a recent special issue of the journal Austral Ecology. The issue, called ‘Greening of arid Australia: new insights from extreme years’, presents papers that investigate how vegetation, small mammal, predator, bird and fish communities responded to the period of well above average rainfall.

‘A clear message emerging from the synthesis is that a combination of broad-scale and long-term monitoring provides the ideal baseline to compare the changes under these extreme climatic years,’ said Glenda, who was a guest editor for the issue. ‘Without that, it is difficult to assess whether the systems have been kicked into a new state with altered function, and uncertain outcomes for native biota.’

Migrations of species outside their known ranges, irruptions of rodents and the redistribution of resources are just a few of the novel observations that have been reported. The transformation of the landscape also presented land managers with challenges stemming from the influx of invasive species that trigger novel ecological interactions and processes.

According to Chris, another of the guest editors, ‘flooding rains are usually thought to be beneficial for all living things in our arid systems, especially after prolonged dry periods. But they also bring great hazards. We recorded huge influxes of feral cats and foxes after the ‘greening event’, to the great detriment of our small native mammals.’

The papers presented in the special issue describe how ecologists and managers responded to the uncommon rainfall events, key lessons that were learnt, and practical recommendations on how to improve conservation outcomes for the fragile inland environment into the future.

For Dr Emma Burns, the executive director of LTERN, what the Desert Ecology Network learned exemplifies the value of research conducted with a long view.

‘All our plot networks in LTERN are invaluable national assets because of their longevity and the knowledge we can generate because of that, allow for the better management of Australia’s natural systems,’ Emma says.

Rainfall for 1–8 March 2011 compared to long-term averages illustrate the extreme rainfalls (400% indicated by dark purple shade) in the continent’s arid and semi-arid regions (Image courtesy of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

Normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI) for Australian continent for the period from 1 September 2010 to 28 February 2011. The dark green shades in the centre indicate high vegetation cover in arid Australia. (Image courtesy of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

Published in TERN newsletter January 2014