Using Australia’s most advanced laser scanner to measure the health of our forests as never before

In the peaceful surrounds of the Karawatha forest in Brisbane’s southern suburbs, along the forest’s ‘echidna track’, sits, quite appropriately but slightly out of place, a bright orange echidna from Boston, USA. ‘Danger, laser in use’ signs hint to passers-by that this isn’t your typical Australian echidna. This echidna is actually the most advanced terrestrial laser scanner in Australia, and one of only two in the world.

Operating the fluoro, giant letterbox-shaped echidna on this warm, slightly rainy, spring morning is Michael Schaefer of TERN’s AusCover facility. Michael, who is based at CSIRO in Canberra, and his team[i] are at Karawatha to scan the forest’s structure as never before and gain a wealth of useful data for future studies.

‘The new echidna laser scanner allows us to obtain unique, accurate and robust vegetation measurements that aren’t possible from other similar laser scanners,’ Michael says.

TERN’s newest piece of research infrastructure, the DWEL, shown here at Karawatha Forest in Queensland (at left, left to right) with team members Peter Scarth, Sabrina Wu, Stuart Phinn and Michael Schaefer; and (at right) being inspected by Michael Schaefer.

The echidna, officially called a dual wavelength echidna lidar (DWEL), contains two lasers of different wavelength that are used to create 3D images of forests in fine detail and provide a permanent record of a forest’s three-dimensional structure at a given growth stage.

During each scan, which takes approximately 45 minutes to complete, the DWEL’s lasers spin and swivel 360 degrees, taking up to 2000 measurements per second of everything within an approximate 60 meter radius. The DWEL is unique in that in one scan it can capture a complete hemisphere, unlike other scanners which require manual changes between scans and the joining of imagery post scanning.

‘Laser scanners like the DWEL are making field work much easier and will save research organisations a huge amount of time and money in the long-run when it comes to man-power for field campaigns,’ says Michael.

The two lasers give maximum contrast between the green leaves and the woody vegetation within the radius, allowing researchers to derive detailed information about the green and woody biomass levels of a forest.

The DWEL system accurately measures the three-dimensional structure and position of a tree, allowing measurement of a number of key dimensions for individual trees, which allows researchers to take detailed and precise data on the vegetation structure – from large tree trunks right down to individual leaves – as well as aiding in placing a carbon storage value on a forest.

Together with AusCover’s suite of terrestrial laser scanners and other equipment for measuring and monitoring vegetation, the new DWELL scanner will be used around Australia to improve continent-scale mapping of Australia’s vegetation [pdf].

‘Improving our continental maps of vegetation is really important as they are often then basis for management planning and ensuring the conservation of our valuable ecosystems,’ says Michael. ‘It’s also important to have a national understanding of vegetation so we can map carbon stocks, which is required under international agreements, such as the Kyoto protocol.’

The week-long stay at TERN’s Karawatha node of the SEQ Periurban SuperSite (part of the Australian SuperSite Network) is the fourth stop on the echidna’s yearlong tour of Australia’s diverse ecosystems.

The echidna’s journey started back in May, when Michael travelled to Boston to personally receive and escort the echidna back to Australia – the quarter of a million dollar price tag helps explain the royal treatment Michael gives his echidna.

On his return to Australia, Michael and his team were itching to start scanning. In June, after a few tests in the CSIRO carpark, they scanned the endangered grassy woodlands of Mulligan’s Flat Nature Reserve , near the ACT/NSW border. The data collected here will be used, initially for calibration of the DWEL scanner, but in the long term it will be used as another method to monitor vegetation structure and fire fuel loads.

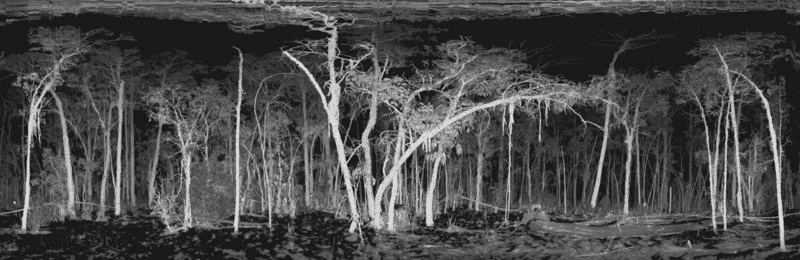

An image of the woodlands of Mulligan’s Flat Natural reserve produced by the new DWEL laser scanner

In July they braved the snow travelled to TERN’s Tumbarumba Wet Eucalypt SuperSite in south-eastern NSW to scan the site’s tall sclerophyll forest. The measurements will be used to evaluate plant growth and canopy cover then combined with data on above-ground biomass, via airborne LIDAR surveys, and hyperspectral data to study forest disturbance after tree harvesting.

In August the team were back in Canberra and scanning some of the 94 ‘forests’ that make up our national arboretum. Here, DWEL images will be supplemented with those from CSIRO’s Zebedee handheld laser scanner to monitor the growth, plant morphology, and health of some of the 48,000 trees including rare, endangered and symbolic trees from Australia and around the world.

Next stop on the echidna’s tour is TERN’s Warra Tall Eucalypt SuperSite in Tasmania. After that they’re off to scan at the Victorian Dry Eucalypt, Calperum Mallee, FNQ Rainforest, and Litchfield National Park SuperSites.

The data from the scans at TERN’s SuperSites around Australia will be made publically available via TERN’s data infrastructure, ensuring that this work is accessible to researchers across the globe.

The progress and whereabouts of the echidna is updated regularly on the DWEL’s online blog. For more information on DWEL please contact Michael Schaefer.

The DWEL has been joint funded by TERN and the CSIRO.

[i] The collaborative field team on hand at Karawatha forest was made up of people from TERN, CSIRO, Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts (DSITIA) and The University of Queensland.

Published in TERN newsletter October 2014