Systematic TERN environmental monitoring systems in a national biodiversity hotspot have allowed identification of an exotic species of grass that nobody had seen for nearly 180 years. Find out how Koeleria macrantha was spotted in Tasmania’s Midlands and what the re-discovery may mean for the region’s ecosystems.

On a chilly afternoon in late November 2019—while many of our readers were in Launceston listening intently to the latest science at the ESA conference—the TERN Field Team was methodically surveying the Tasmanian Midlands national biodiversity hotspot.

In addition to recording all vegetation present and soil characteristics, the team collected hundreds of samples for expert identification, analysis and researcher access.

The TERN Ecosystem Surveillance plot where the weed was found is located in an open manna gum woodland (Eucalyptus viminalis Labill. subsp. viminalis) with a very dense ground storey of Lomandra longifolia.

A month or so later, Miguel de Salas, Senior Curator at the Tasmanian Herbarium, made a startling discovery among the plant samples. Miguel had just identified a weed species not seen in the State since the early 1800s: Koeleria macrantha.

“As soon as I saw the specimen, I had my suspicions. But because Koeleria macrantha is listed as extinct in Tasmania I got a second opinion from my colleague who’s a grass species expert.

The species is now naturalised in New South Wales and the ACT, but the last verified specimen of the species in Tasmania was found in November 1842.

We had a match. The TERN November 2019 sample matched the one we had from 177 years earlier. We had re-discovered Koeleria macrantha in Tasmania.”

Miguel de Salas, Tasmanian Herbarium

Koeleria macrantha is now naturalised in New South Wales and the ACT, but the last verified specimen of the species in Tasmania was found in November 1842 (Credit: Wikimedia Don Pedro28 / CC BY-SA)

TERN surveys turn up things that others overlook

Miguel says that the latest weed discovery further demonstrates the value of TERN’s systematic monitoring of all species, followed up with retention and formal identification of voucher specimens—as per the TERN AusPlots Rangelands Survey Protocols Manual.

“It’s great to have these surveys, that record absolutely everything at a site, in an area or a property because you turn up things that a targeted survey might never pull up.

Collecting specimens results in physical proof. The vast majority of surveys that get done are anecdotal observations only. They write what they see, and then 20 or 30 years down the track that data becomes useless because you have no way of verifying the observations.”

Miguel de Salas, Tasmanian Herbarium

Finding bodes well for national biodiversity hotspot

Associate Professor Ben Sparrow of TERN’s Ecosystem Surveillance platform says that the location of the find is not the environment that probably comes to mind when you think of Tasmania.

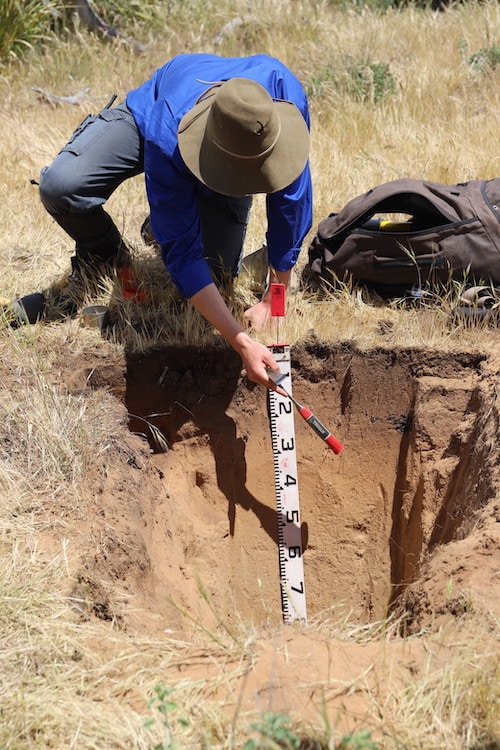

“For starters, it sits on a relic sand dune so the soil at the site is a very deep loamy sand, which is very different to the more typical heavier soils through the rest of the Midlands.

We don’t know, but this could have something to do with why it has persisted there and not elsewhere.”

Ben Sparrow, TERN Ecosystem Surveillance

In terms of vegetation, the site is located in an open manna gum woodland (Eucalyptus viminalis Labill. subsp. viminalis) with a very dense ground storey of Lomandra longifolia—a grass often used on roadside plantings around Australia.

TERN’s Field Team conducting soil analyses at the Midlands site where the weed re-discovery was made

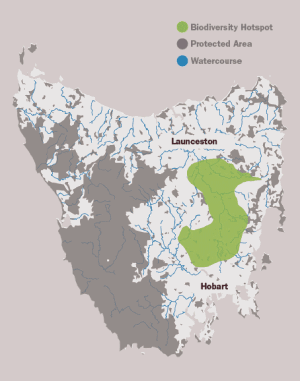

The Midlands site is located in one of Australia’s 15 national biodiversity hotspots—areas with high concentrations of species that are endemic (unique) to each region and which are threatened with destruction.

Whilst the potential impacts of Koeleria macrantha on the hotspot’s native plant diversity are unknown, Miguel says that, counterintuitively, the weed’s re-discovery is most likely a good thing.

The most important thing is that it’s not that weedy and unlikely to spread like crazy.

I suspect that there must be small populations hanging on here. So, now that we know it’s out there again we can manage it appropriately and prevent it from turning into a bigger environmental problem.”

Miguel de Salas, Tasmanian Herbarium

The location of the Tasmanian Midlands national biodiversity hotspot (credit: Bush Heritage Australia)

Future repeat TERN surveys at the Midlands sites will detect any significant increases in frequency or abundance of the species, a finding that could trigger more targeted monitoring or management.

So, watch this space for more updates on Tasmania’s grassy interloper.