This month we’re pleased to hear from Aaron Greenville from our Long Term Ecosystem Research Network (LTERN) and partner organisation The University of Sydney, about a new study that will have implications for how we manage introduced cats and foxes and control their costly impacts on rangeland grazing operations

A surveillance operation is underway in one of the most remote parts of the Australian continent. For 24 hours a day over the course of more than two years the lives of three species of predator have been watched, documented and now published. Over this time the Simpson Desert has experienced a rare, yet amazing event: the rains came and it boomed! How did this boom in rodent prey affect our three predators, but more importantly, how did this boom influence the interactions between them? What was the role of the dingo, Australia’s only native canid, in suppressing the feral red fox and cat? These two smaller predators, or mesopredators, have had a drastic effect on the native animals of the interior. Many of these unique native species are now extinct.

The mesopredator release hypothesis

The mesopredator release hypothesis predicts that dominant, usually larger, predators will suppress their subordinate counterparts but, if removed, the mesopredators will be “released” from competition or direct interference; increases in their numbers then may lead to increased impacts on small prey. A classic example is the grey wolf that can suppress coyotes in North America. More recently, the lynx has been shown to suppress the fox in Eurasia and in Australia the persecution of dingoes may allow feral cats and foxes to increase in number. The impact of predation from feral cats and foxes on Australian native wildlife has been well documented. For example, at least 34 threatened species have been identified as at high risk from cat predation.

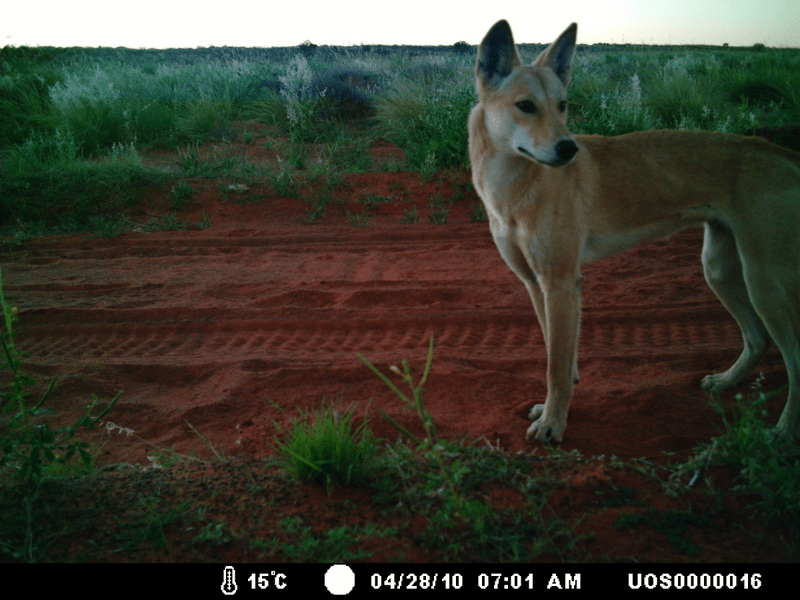

A dingo pauses in front of a remote camera trap set up to monitor predators in the Simpson Desert, Australia.

Booms and busts in prey

There has been a long debate in ecology about the importance of bottom-up effects, such as booms in resources and prey abundance, versus the top-down effects of predators. More recently, these two schools of thought have been combined and both are acknowledged as important influences on species populations. The deserts of the world are a great place to study this interaction between bottom-up and top-down effects. Desert populations generally tick along slowly, but every now and then, maybe every 10 years or more in central Australia, flooding rains fall and the desert blooms – and booms! This massive increase in food flows as energy through the ecosystem, and how this changes or modifies interactions between dominant predators and mesopredators (smaller predators) is something we wanted to find out.

A thief is caught during the night stealing a native rodent (most likely a sandy inland mouse, Pseudomys hermannsburgensis). Feral cats have had a drastic impact on Australia’s native wildlife.

Remote camera traps

To answer this question we needed to use a method to monitor populations of dingoes, cats and foxes. We cannot be in the field all the time, but a remote camera can. Remote camera traps are activated by movement (and sometimes heat, depending on the model). Once activated, they lie in wait 24 hours per day and when an animal walks past, the trap is triggered. The trap results in a photograph of the individual, with the time, date, temperature and moon phase recorded. This information can be used to build a picture (pardon the pun) of what time the animal is most active and how many are in an area. All this information is gathered without any interference to the animals.

After a flooding rainfall event, rodent numbers plague. These individuals were caught on a remote camera trap in the Simpson Desert.

What we found

The interaction between dingoes and the smaller introduced predators is more complex than first thought. During droughts, dingoes suppressed the introduced red fox and cat, with fewer photographs of these smaller predators being recorded with increasing numbers of photographs of dingoes (top-down effects). As populations of rodent prey boomed in number, this relationship broke down and all predator populations increased with the increased availability of prey (bottom-up effects). As prey populations declined and fell back to drought levels, the interaction between dingoes and the smaller introduced predators began again.

Setting up a remote camera trap in the Simpson Desert. These cameras monitor the ground for any movement and take a photograph, with the date and time. This information is very useful for a researcher. (Photo courtesy of Alan Kwok).

Implications

These findings have implications for how we manage introduced cats and foxes, and also dingoes. Dingoes are still persecuted across Australia due to their impact on livestock. Land managers spend a great amount of time and money implementing control programs to limit the populations of all three predators, but there is a cheaper and easier way. The dingo is an un-paid pest species manager that works every day. By leaving them alone, they can help control populations of cats and foxes for free! Land managers can concentrate their pest species control programs for the period after large rainfall events in central Australia. Imagine pooling resources that are spent every year on controlling cats and foxes in central Australia being used every 10 years or more i.e. the frequency of large rainfall events in central Australia. In the dry times the dingo may be able to do the work for us.

Dingoes will attack livestock and industry-funded reports suggest this costs AUD$ 48 million to AUD$ 60 million annually. Currently, lethal control methods are used to deter livestock attack from dingoes, but history has taught us a deadly lesson if we continue to follow this old idea. Alternatives to lethal control do exist. Guardian dogs can protect stock from dog attack and return the investment on them between one to three years later. These new ideas need to be trialled in central Australia

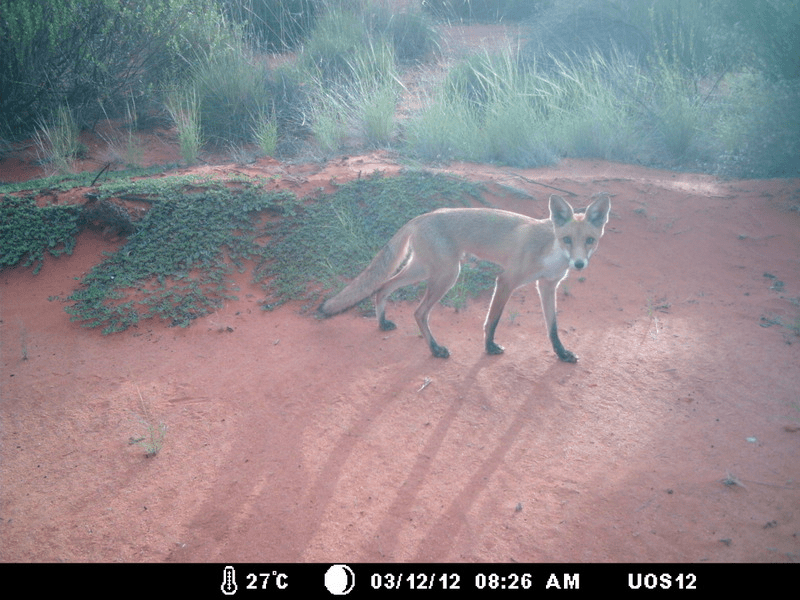

An introduced red fox is captured on a remote camera trap in the Simpson Desert, Australia. The dingo may be able to help us control the numbers of this predator in central Australia.

This project was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award, Paddy Pallin Grant, Royal Zoological Society of NSW, the Australian Research Council and by TERN.

Data from LTERN’s Desert Ecology Network can be found on the LTERN data portal or via TERN’s Data Discovery Portal. This article was originally published on Aaron’s personal blog and can viewed here.

Published in TERN newsletter November 2014