Australia’s alpine ecosystems may be particularly vulnerable to changing patterns of climate, fire and land-use pressure in the coming century. Using environmental sensors to document environmental change, and deciding how best to manage the land for sustainable use, requires detailed knowledge of the fundamentals of ecosystem structure and function – insights that we now possess thanks to decades of persistent ecological monitoring effort in the Australian Alps.

The network of long-term alpine ecosystem monitoring sites, some of which were established in the 1940s, is now supported through TERN’s Long-Term Ecological Research Network, a sub-facility of the Multi-Scale Plot Network. Data from these sites underpin our understanding of the dynamics of Australian alpine ecosystems, and have enabled researchers to identify combinations of factors that put these systems at risk.

Dr Dick Williams from CSIRO has been working on these sites for 32 years. ‘Long-term monitoring will always be vital for increasing our understanding, anticipating change and managing the alpine environment for sustainability. The understanding gained from this research has also highlighted its limitations: 60 years is a short time in the Alps, and there are still many things we don’t understand.’

So what have we learned from the long-term monitoring data, and how is this knowledge helping us more sustainably manage land use in the Australian Alps?

Documentation of the unique character of alpine vegetation from six decades of research has had a major influence on the establishment of conservation reserves, such as Kosciuszko National Park in NSW, and Alpine National Park in Victoria. These data will continue to inform national park management in the coming decades.

‘We’ve learned a lot about vegetation dynamics, and the distribution, population structure and reproduction of important species, such as the rare and endangered mountain pygmy possum,’ says Dick. The mountain pygmy possum (Burramys parvus) is an iconic alpine species, and is listed under both Commonwealth and State legislation. The good news is that monitoring data indicate that Burramys is persisting in the alpine landscape, and most populations appear to be recovering after the 2003 Victorian fires. Data on the population and breeding biology of Burramys have been used extensively to direct major conservation management programs in ski resorts, for example at Mt Buller and Mt Hotham, for over two decades.

Mountain pygmy possum (Photo courtesy of Cate Aitken, NSW National

Parks, Office of Environment and Heritage)

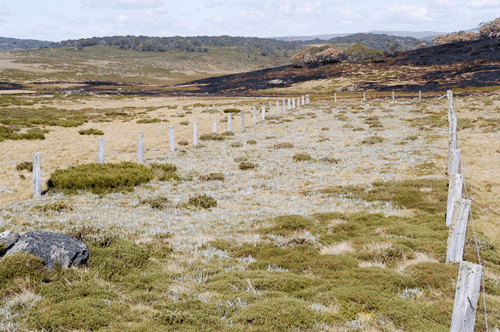

Data from the long-term monitoring sites also provide clear answers to questions about the impacts of disturbance on alpine ecosystems. For example, cattle grazing, and its cessation, have both had profound effects on alpine ecosystems.

‘Cattle grazing changes species composition, alters ecosystem dynamics, and degrades plant communities, for example by reducing the abundance of palatable herbs such as species of Craspedia and Celmisia,’ says Dick.

As a consequence of these long-term research results, grazing of sheep and cattle has been gradually phased out of most alpine areas.

‘But, where grazing has ceased, we have been able to document recovery of all major alpine ecosystems – grasslands, herb fields, heathlands and wetlands,’ Dick says.

Long-term plots have also been established to look at post-fire regeneration.

‘Alpine vegetation has proved remarkably resilient to the 2003 fires,’ adds Dick. ‘We would not have been able to come to this view so quickly were it not for the long-term plots.’ The long-term plots have also been invaluable for interpreting the changes seen in a recent warming experiment undertaken on the Bogong High Plains over the past decade, as part of the International Tundra Experiment.

‘This network of plots and experiments will allow us to look at how climate change, fire and past grazing interact. Our predictions are that the more healthy and otherwise undisturbed an ecosystem is, the better it’s going to be able to recover from future changes to climate and fire regimes,’ says Dick. ‘The long-term perspective the plots provide is vital if we are to devise appropriate conservation management strategies for alpine landscapes for the next century.’

The Pretty Valley monitoring plots on the Bogong High Plains in Victoria. The plots were established in 1946–47, and were last monitored in 2009. The vegetation inside the fence has not been grazed by cattle since the plots were established. The companion grazed plot is to the left of the left-hand fence. The photo was taken soon after the extensive fires of 2003. (Photo courtesy of Henrik Wahren)

Published in TERN e-Newsletter August 2012