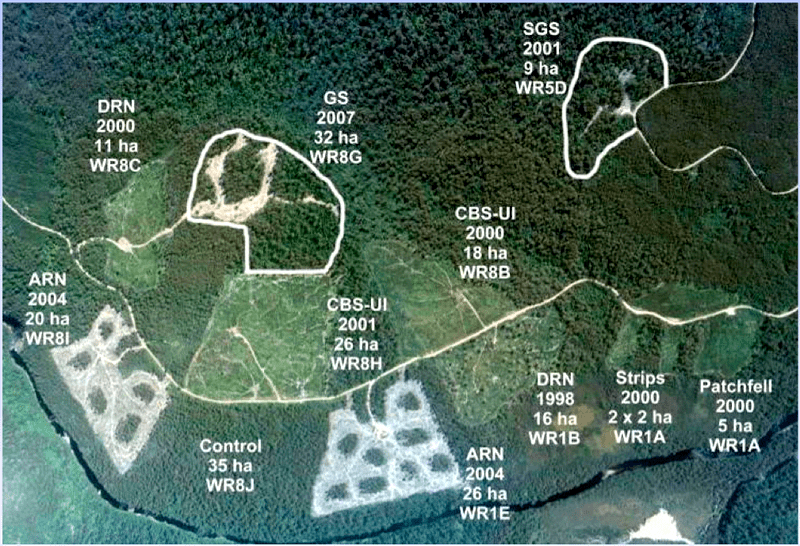

An aerial image of the Warra Silvicultural Systems Trial (SST). CBS-UI: Clear-fell, burn & sow with understorey islands; DRN: dispersed retention; ARN: Aggregated retention; GS: group selection; SGS: small group selection (image courtesy of Tim Wardlaw).

Research at long-established TERN environmental monitoring sites in production forests sheds new light on interactions between logging practices, carbon stocks and biodiversity protection and leads to improvements in forestry practices

At TERN’s Tumbarumba Wet Eucalypt SuperSite in NSW’s Bago State Forest, and Warra Tall Eucalypt SuperSite in Tasmania, research has been occurring alongside logging operations for more than 15 years. The value of this long-term ecosystem science research in these production landscapes is reaping rewards for both conservation and forestry.

Tumbarumba Wet Eucalypt SuperSite, managed in partnership by TERN’s OzFlux and Australian Supersite Network facilities, is one of the few southern hemisphere sites that has provided records for longer than a decade of the weather, climate, net uptake of CO2 and loss of water via evapotranspiration in a managed, open wet sclerophyll eucalyptus forest.

Apart from continuously measuring the exchanges of carbon dioxide and water vapour between the forest and the atmosphere, Tumbarumba has been the site of various intensive measurement campaigns to improve our understanding on how airflow, terrain and forest structure affect the way the ecosystem takes up and releases carbon and uses water.

As part of this effort CSIRO has carried out independent measurements of carbon pools, stocks and turnover rates. These measurements, along with atmospheric fluxes, have been used to improve the surface–vegetation–atmospheric–transfer (SVAT) models. SVAT models describe how energy, carbon and water are exchanged between land and atmosphere, and Tumbarumba has played a major role in improving SVAT modelling in Australia over the last decade.

With logging currently occurring at the site, research is improving understanding of how logging practices affect the amount of carbon and water entering, stored in and leaving the forest, and how these factors in turn influence the ecosystem as a whole.

Further south at TERN’s Warra Tall Eucalypt SuperSite in Tasmania, research has led to a better understanding of how harvesting methods for use in tall, wet eucalypt forests can meet social, ecological and silvicultural objectives while still being safe and productive.

The project that led to forestry practices becoming more sophisticated and sensitive to wildlife and human social needs, the Silvicultural Systems Trial (SST), began in 1998. There was a major review of the SST in 2008 when most ‘treatments’ (that is, clear-fell, burn and sow (CBS), aggregated retention and so on) had reached their third anniversary after harvest. Researchers found that communities of birds, ground beetles, and plants had changed markedly in the harvested areas of all treatments, but remained similar to unharvested forest in the retained forest patches within aggregated retention and strip-fell treatments. While eucalypts regenerated best in CBS, most other treatments reached acceptable stocking levels by age three.

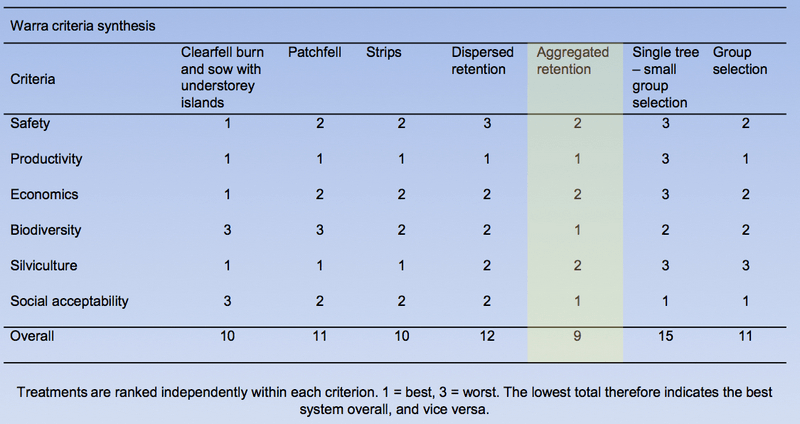

A summary of the results of the Warra Silvicultural Systems Trial (SST) as published in Neyland et al. (2012) Australian Forestry, 75(3): 147-162

Convinced by the research results, Forestry Tasmania developed practical ways to do aggregated (or variable) retention so it could be adopted as a harvesting method for use more widely.

Dr Tim Wardlaw is one of the scientists who has been studying ways of improving forestry and its social acceptability while protecting biodiversity. He manages the Warra site, which is part of TERN’s Australian Supersite Network.

‘Translating the scientific findings from the SST into policy and practice meant bringing together scientists, planners and operations staff to develop feasible practices that achieved the ecological, economic and social objectives,’ Tim says.

‘Among other things, we had to evaluate the harvesting operations. At the end of four years of using aggregated retention we found that we could successfully harvest trees, protect the patches of mature forest retained in the aggregates, and provide good conditions for regeneration in the harvested areas. We will keep monitoring forest in the Silvicultural Systems Trial to see if late-successional species recolonise the harvested areas in variable retention areas faster than in CBS. This monitoring acts as a sentinel to tell us when to monitor more widely in areas harvested.’

The next review of the SST is planned for 2015, when most treatments reach their 10th anniversary.

In other research at the Warra SuperSite, scientists found that, 30 to 50 years after harvesting, production forests can support similar populations of many mature-forest species as mature undisturbed forests, if sufficient mature forest remains in the surrounding landscape.

‘Knowing this helps us determine how to balance harvesting and retention in politically and ecologically sensitive areas of tall, wet eucalypt forest,’ Tim says. ‘We tested this along a gradient of forest environments, contrasting the biodiversity of largely pristine landscapes with that in increasingly altered landscapes, that is towards the farming end of the scale. The results are crystal clear: if there is sufficient mature, undisturbed forest nearby, the harvested forest can return to something akin to its original state.’

Tim said the research has vindicated the approach for biodiversity conservation developed for the regional forest agreements that Commonwealth and state governments signed in the 1990s. The combination of a comprehensive, adequate and representative (CAR) reserves and complementary management outside reserves is used to sustain forest-dependent species throughout their range. .

‘The CAR reserves aren’t distributed evenly throughout the landscape – for example, many of the large, formal reserves abut national parks, where there is already a high level of protection – but we found that uneven distribution didn’t really matter. Mature forests remaining in the more intensively managed production forest areas have similar populations of species as those in and around the large reserves. It shows we can manage biodiversity and human consumptive needs in forestry areas,’ Tim says.

This knowledge will be used to fine-tune forest practices and forest policy, to ensure that biodiversity is conserved.

The Warra Tall Eucalypt SuperSite is supported by TERN, Forestry Tasmania, CSIRO, the University of Tasmania, the Tasmanian Government, the Department of Agriculture, and the Forests Practices Authority.

AusPlots monitoring plots are also installed in the immediate area around the Warra SuperSite, and monitoring data will be available through TERN’s Eco-informatics facility, which manage the data using its ÆKOS data repository.

The Tumbarumba SuperSite is supported by TERN, CSIRO and the Department of Environment through the Australian Climate Change Science Program (ACCSP).

Published in TERN newsletter November 2014